Sunday, December 15, 2013

Aerial Views, Camouflage & Crazy Quilts

After World War I began, camouflage was widely adopted, and inevitably there were comparisons of camouflage and cubism, and, in turn, of camouflage and crazy quilts. More serious, and far more interesting as well, were the various many comparisons of cubism, camouflage, crazy quilts and views of the earth from an airplane (a novelty then). Here's what Ernest Hemingway said in "A Paris-to-Strasbourg Flight" in the Toronto Daily Star on September 9, 1922—

The plane began to move along the ground, bumping like a motorcycle, and then slowly rose into the air. We headed almost straight east of Paris, rising in the air as through we were sitting inside a boat that was being lifted by some giant, and the ground to flatten out beneath us. It looked cut into brown squares, yellow squares, green squares and big flat blotches of green where there was a forest. I began to understand Cubist painting.

Of course Hemingway wasn't the only one to make such comparisons. Journalists and the general public saw it too. Below are two aerial photographs of the French landscape from the same time period. The second view, which appeared initially in Collier's Weekly in 1918, was captioned with a text that read—

NO WONDER CUBISM STARTED IN FRANCE! No one need wonder any longer where the cubists got their inspiration. They must have gone up in an airplane and had a good look at France! This airplane view of an observation balloon floating over a French village is as good a bit of cubist art as anything that Marcel Duchamp ever turned out.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Cubism Meets Camouflage

|

| John French Sloan, Cubist Cartoon (1913) |

It is usually claimed that cubism began around 1907 in Paris, but it was not widely introduced to the American public until 1913, when an International Exhibition of Modern Art (known as the Armory Show) premiered in New York from February 15 to March 15, then traveled on to Boston and Chicago. On the day after its opening, a headline in the Magazine Section of the New York Times read “Cubists and Futurists Are Making Insanity Pay.” Cartoons and jokes about cubism became epidemic, as in this example by American artist John French Sloan (1871-1951), first published in 1913. Throughout World War I, cubism, futurism, vorticism and camouflage (dazzle ship camouflage in particular) were said to be related, and were all commonly compared to crazy quilt patterns, harlequin outfits, aerial views of cultivated land forms, and the hallucinations of absinthe drinkers.

Sunday, July 24, 2016

Roland Penrose | Cubism, Illusion and Camouflage

|

| Roger Penrose, Impossible Triangle |

Roland Penrose was an early important biographer of Pablo Picasso. He was greatly interested in cubism, which is frequently said to resemble disruptive, dazzle or "high difference" camouflage. Perhaps not surprisingly, he was also involved in wartime civilian camouflage. During WWII, he teamed up with other artists (notably Stanley William Hayter, John Buckland Wright, and Julian Trevelyan) in founding a company that provided questionable camouflage for industrial landmarks. Later, he taught camouflage and compiled an instructional guidebook, titled Home Guard Manual of Camouflage (October 1941), the cover of which is shown below.

Related to this, there is a passage from Penrose's notebooks, published in Elizabeth Cowling, ed., Visiting Picasso: The Notebooks and Letters of Roland Penrose. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2006, pp. 245-246, in which he talks about Picasso's reaction when he first saw (Penrose's nephew's) the impossible triangle in 1962—

Showed P[icasso] the impossible triangle. He looked at it, puzzled for some minutes, then started making other versions of it. "Your brother [sic] should have been a cubist," he said. "It's an attempt to catch the 4th dimension. They always say the cubists were trying to catch the truth—they were really trying to make a deception—just like this—cubism was full of deception. Your brother [sic] should have worked with us; we would have found a lot in common."

|

| Roland Penrose book cover (1941) |

Thursday, February 2, 2023

cubism and camouflage / oscillation of appearances

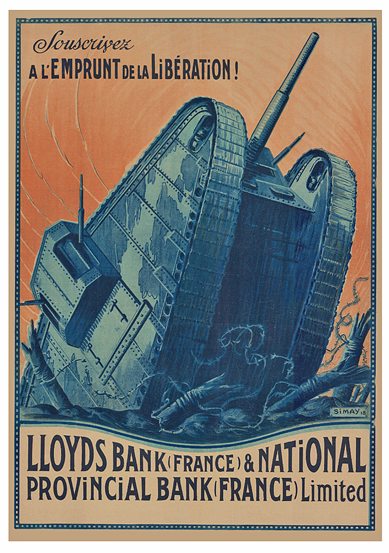

Above Simay Imre, Subscribe to the Liberty Loan (World War I French poster), 1918. University of Illinois Archives, Public Domain.

•••

Wylie Sypher, Rococo to Cubism in Art and Literature. New York: Vintage Books, 1960—

To prove that art and life intersect, that thought enters things, that appearance and reality collide, or coincide, at the points we call objects, the cubist relied on certain technical devices: a breaking of contours, the passage, so that a form merges with the space about it or with other forms; planes or tones that bleed into other planes and tones; outlines that coincide with other outlines, then suddenly reappear in new relations; surfaces that simultaneously recede and advance in relation to other surfaces; parts of objects shifted away, displaced, or changed in tone until forms disappear behind themselves. This deliberate “oscillation of appearances” gives cubist art its high “iridescence” [p. 270].

It has been said that the great cubist achievement was camouflage [p. 299].

RELATED LINKS

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

Gestalt Theory, Cubism and Camouflage

Above Cover of Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye by Harvard psychologist and art theorist Rudolf Arnheim (1904-2007). Having studied with Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler at the University of Berlin, he was the last surviving student of the founders of Gestalt psychology.

* * *

Max Wertheimer and Pablo Picasso were contemporaries: The former, who co-founded Gestalt theory with Kurt Koffka and Wolfgang Köhler, was born in 1880; while the Spanish painter, who invented cubism with Georges Braque, was born in 1881. Both Gestalt theory and cubism emerged in the years that preceded World War I. Gestaltist Fritz Heider does not suggest that Wertheimer and Picasso were acquainted, or even that they knew about each other's discoveries, but only that "the perceptual phenomena with which they were dealing were the same" (Heider 1973, 71). However, it also seems likely, as he points out, that both realized that the factors that they were exploring were used in military camouflage. More…

Wednesday, December 23, 2020

Designer John Vassos / WWII Camouflage Consultant

John Vassos, c1932

Above Art Deco-era turnstyle, designed by John Vassos, c1932. We blogged about Greek-American designer John Vassos a few years go in reference to his service as a camouflage consultant during World War II.

•••

CUBISM DOMINATES NEW PARIS SALON ARTISTS, in Bluefield Daily Telegraph (Bluefield WV), September 19, 1926, Section 2, Page 4—

Paris, Sept 18—Cubism completely dominates the new Paris Salon of decorative artists. The curve must only be used in case of grave necessity. Straight lines, angles and zigzags dominate tables, chairs, lighting, jewelry, clocks, and, above all, architecture. Even carpets and curtains have to fit octogonal rooms, and are cut up themselves into tee-squares and triangles.

Chairs look as though they were cut out of solid cubes of wood and then camouflaged with a medley of colors. Curtains are often painted by hand in vivid thunder and lightning effects. The edges are made of strips of different color, each of which is a littler shorter than the last, like the ABC of a diary. Clocks are made entirely of glass, but have square faces, and are supported by glass stands cut like a Chinese puzzle. Heading lamps are equally geometrical problems. Colors are almost as angular, consisting of vivid greens, purples, magnates, raw siennas, sometimes all mixed together. The new Decorative Salon is nothing if it is not revolutionary.

Monday, September 5, 2016

Futurist Views: Nevinson, Bertram Park and Dazzle

|

| C.R.W. Nevinson (1919) |

As striking as Nevinson's work may be, neither it nor he were ever immune to being satirized in the public press, who always had trouble accepting the use of disruption, distortion and abstraction in styles of Modernism (Cubism, Futurism, Vorticism). This attitude persisted (and still persists, to large extent) even after art defenders claimed that those were precisely the methods employed in the design of disruptive wartime camouflage, called dazzle-painting.

For example, reproduced below is an innovative photographic portrait of Nevinson, which appeared in The Sketch (May 21, 1919, p. 143), on a page that bears the headline A "CUBIST" CUBED—BY THE CAMERA. Beneath the photograph, there is a smaller heading that reads Nevinson—Reduced to His Own Artistic Formula.

|

| Portrait of C.R.W. Nevinson by Bertram Park (1919) |

As it turns out, this experimental photograph was made by none other than Bertram Park, a well-known British society photographer (somewhat avant-garde himself), whom we have previously blogged about in relation to his photographs of the outlandish costumes at the Chelsea Arts Club Dazzle Ball. Below the Park photograph, we are provided with the following caption—

Before the war, Mr. C.W.R. Nevinson was associated with the Futurist movement in art, but his peculiar style of cubism and realism combined was not developed until 1916, when he held his first War Exhibition, and was appointed an official war artist. He has painted pictures for the Canadian War Memorial, and many of his works have been bought by museums—at home and abroad. The above photograph of the Cubist artist by a camera converted to Cubist convention was taken recently, before Mr. Nevinson sailed for America. It is, to say the least, unconventional.

•••

That same year, in the August issue of Current Opinion, Park's photographic portrait of Nevinson was reprinted (as shown below) in a two-page feature on Nevinson's assertion that Cubists and Futurists Had a Presentiment of the Coming Conflicts. Appearing in the magazine's section on Literature and Art, the headline for the article was HOW THE WAR VINDICATED "MODERN" METHODS IN ART.

As quoted from an interview in the Times, here is part of what Nevinson said—

This war did not take the modern artist by surprise—it only knocked the old fellows, who were tied up to old ideals of art, off their feet. I think it can be said that modern artists have been at war since 1912. Everything in art was a turmoil—everything was bursting—the whole talk among artists was of war. They were turning their attention to boxing and fighting of various sorts. They were in love with the glory of violence. There were dynamic, Bolshevistic, chaotic.

…Everything was being destroyed; canons of art were everywhere sacrificed. And when the war actually came, it found the modern artist equipped with a technique perfectly able to express war.

…Now that art has had its orgy of violence there has been an abrupt reaction. The effect of the war has been to create among artists an extraordinary longing to get static again. Having been dynamic ever since 1912, they are now utterly tired of chaos. Having lived among scrap heaps, having seen miles of destruction day after day, month after month, year and after year, they are longing for a complete change.

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

Model of USS Agwidale in Dazzle Camouflage

•••

Anon, from the Bradford Era (Bradford PA) on April 5, 1918—

The staunchest upholders of the academic in art can scarcely carry their opposition to cubism into its new field as a basis for camouflage. It has been evident, for some time, to people living near Atlantic ports, that cubism has been pitched open as the most valuable system of reducing the visibility of ocean liners. The seemingly systemless way in which greens, blues, grays, and pinks are panted on in bands and blocks of color has quite puzzled persons who have gained close views of these ships; but at a distance of a mile, another story is told, for the various masses of color set up a curious and disconcerting dazzling effect. Painting with gray has been largely superseded by the new method, which escapes the silhouette effect that too often betrayed the gray ships.

Sunday, May 31, 2020

Art | an illusion of reality that tells the truth by fibbing

|

| Leon Dabo (1909) |

•••

Rollin Lynde Hartt, CAMOUFLAGE in Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1918—

As their train nears Chicago, passengers note a low, murmurous hum. It is the Chicagoans saying “Camouflage.” Those of us who once confined our remarks to “Skiddoo! Twenty-three!” and more recently to “I should worry!” and “What do you know about that?” peg along at present on “Camouflage,” though a bit wearisome it grows. Declares a neighbor of mine, “The next time I hear ‘Camouflage’ I shall make my will, kiss my friends and relatives good-bye, and jump in the wastebasket!”…

[Camouflage] borrows its technique from a humble enough source. It is the Chamber of Horrors over again…Some steal their technique from the impressionists. Some repeat the antics of cubism. Others depend for their success upon certain very curious principles of optics. It takes an artist to invent them and an artist to explain them, and Mr. Leon Dabo* is never more entertaining than when holding forth on their theory and practice.

In order to understand the enormously important part impressionism plays in camouflage one must first define impressionism. Aesthetically, it is a simple matter, merely an attempt to reproduce, not nature itself, but the side of nature that appeals strongly to the artist. Technically, however, it involves profundities. Instead of counterfeiting reality, it creates an illusion of reality. It tells the truth by fibbing…

It was to cubism that the camouflageurs had recourse when they wanted to hide ships from view. Painting them gray was a poor device, they found. From habit, the eye would still recognize the silhouette of a ship even at a great distance. But it turns out that the eye had come to depend almost wholly on habit. Break up the familiar silhouette by dappling it with inharmonious colors in huge, shapeless masses, or—better yet—by covering it with immense cubist triangles and with cubist rectangles as immense—and the eye of the seasoned mariner would report no ship at all. The eye sees what it is accustomed to seeing and balks at learning new tricks.…

And why resent that low, murmurous hum of the Chicagoans saying “Camouflage”? Let the hum continue. It is just now a foolish hum, to be sure; it reflects a quaintly naive sense of novelty, as if camouflage were a new thing under the sun instead of being a modern recourse to trickery as old as “Quaker” cannon and the painted portholes on merchantmen, and, for that matter, the celebrated wooden horse at Troy. But it popularizes an idea. It gives it prominence. It backs up the army’s determination to put camouflage where it belongs. France has thousands of camouflageurs. So should we.…

•••

* Note The following entry was featured in a column titled Fifty Years Ago 1918, in the August 25, 1968 issue of the Asbury Park Press (Asbury NJ)—

Aug. 27—Leon Dabo, American painter who has been serving on General Pershing’s staff designing camouflage, was the principal speaker at a war rally in Ocean Grove Auditorium. He described enemy atrocities.

Friday, August 15, 2025

Picasso, camouflage, and the moth known as Picasso

Above This is, believe it or not, an insect called the Picasso Moth, known scientifically as Baorisa hieroglyphica. It was discovered by the British entomologist Frederic Moore in 1882, when artist Pablo Picasso was one year old. Surely, it was given his name (probably after World War I) because people came to believe (thanks to Gertrude Stein in part) that he had invented wartime camouflage. Not so, but the error continues. That assumption was emboldened by rumors (as in quotes below) during WWII that Picasso had somehow served as a camouflage advisor for the French government.

That there are resemblances between certain aspects of Cubism and WWI camouflage is undeniable. And yes, Picasso (and untold others) saw those resemblances. But he did not originate the practice during WWI. See my earlier online essay on this.

•••

Anon, from Le Devoir (Montreal), May 30, 1940—

The godfather of camouflage

Camouflage, which has truly become an official weapon of war since there are now regular sections to which specialists are attached, is a French invention of the other war. It began with the substitution of conspicuous uniforms, from red, to blue and gold, to horizon blue, to the colors of the earth and the sky, then to khaki, less messy, and especially less lamentable as it becomes increasingly worn.

What few people know is that the official godfather of camouflage is none other than the inventor of cubism, Pablo Picasso. An official asked that artist, with tongue in cheek, for his advice on how to make men invisible to the enemy. Picasso, in all seriousness, replied, "Dress them as harlequins..!" It was a joke which others took seriously and was soon adopted, for it is indeed in harlequin patterns, in effect, that the factories, the cannons, the vehicles, and even the ships, are now disguised.

•••

Anthony Marino, in “He’d Like to Hear What Artists Think,” a letter to the editor in The Pittsburgh Press, November 26, 1944—

I was not surprised when [Pablo] Picasso was placed at the head of the camouflage department in France; nor when [Homer] St. Gaudens was placed at the head of the same department in this country. Both were given the job of making “something” look like “nothing.” Both had already demonstrated their aptitude at the much more difficult task of making “nothing” look like “something!”

RELATED LINKS

Dazzle Camouflage: What is it and how did it work? / Nature, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Women's Rights, and Camouflage / Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Gestalt, and Camouflage / Optical science meets visual art / Disruption versus dazzle / Chicanery and conspicuousness / Under the big top at Sims' circus

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

Tuesday, March 19, 2024

Juan Gris / World War One has been kind to the cubist

Above I have long believed that the truly great practitioner of Cubism was neither Pablo Picasso nor Georges Braque, but rather the all-but-neglected Juan Gris (1887-1927). Above is his remarkable Portrait of Pablo Picasso (oil on canvas, 1912, Art Institute of Chicago). In this painting, the liquidity of the background pretends to threaten the figure, but it always backs off without doing serious damage. Gris must have been prolific because he seems to have produced so much artwork of such heightened quality, and yet he died at forty.

•••

THE CUBISTS’ CHANCE in Ardmore Daily Ardmoreite (Ardmore OK). August 31, 1918, p. 4—

The war has been kind to the cubist artist. He has his day at last. Timid souls who dared neither to scorn nor praise the sylvan views and staircase scenes of the cubist can now burst forth in unstinted praise of these same designs when painted upon gun timbers, freight car doors and ships, to hide them from the enemy.

Camouflage would seem by divine right to be the cubist’s field. As he once successfully disguised the scenes he claimed to depict, he may now conceal the very surface on which he lays his paint. And the entrancing thing is that the layman can appreciate and enjoy the work quite as much as the artist, which he could not do in the glorious days of cubism recently passed.

RELATED LINKS

Dazzle Camouflage: What is it and how did it work?

Art, Women's Rights, and Camouflage

Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage

Thursday, June 15, 2017

Devising Dazzle Camouflage by Isolating Details

|

| Hypothetical dazzle schemes |

•••

Anon, "Cubism in War" in the New York Tribune, Sunday, September 15, 1918, p. 6—

Baffle painting is the latest development of marine camouflage, the idea being not to make the ship invisible, but to break up all accepted forms of a ship by masses of strong contrasting colors, distorting her appearance so as to destroy her general symmetry and bulk, the result being to keep the U-boats guessing as to whether she is "going or coming." A practical use has been found for cubism, after all.

Friday, April 22, 2022

Picasso on camouflage / we originated it with cubism

|

| Cook: The Man Who Taught Gertrude Stein to Drive |

•••

Gertrude Stein (speaking in the pretended voice of Alice B. Toklas), The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1933—

[In 1907, Pablo Picasso went back to Spain for the summer] and he came back with some spanish landscapes and one may say that these landscapes…were the beginning of cubism.…

…In these pictures he first emphasized the way of building in spanish villages, the line of the houses not following the landscape but cutting across and into the landscape, becoming undistinguishable in the landscape by cutting across the landscape. It was the principle of the camouflage the guns and the ships in the war. The first year of the war, Picasso and Eve, with whom he was living then, Gertrude Stein and myself, were walking down the boulevard Raspail a cold winter evening.…All of a sudden down the street came some big cannon, the first any of us had seen painted, that is camouflaged. Pablo stopped, he was spell-bound. C’est nous qui avons fait ça, he said, it is we that have created that, he said. And he was right, he had. From Cézanne through him they had come to that. His foresight was justified.

RELATED LINKS

Dazzle Camouflage: What is it and how did it work? / Nature, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Women's Rights, and Camouflage / Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Gestalt, and Camouflage / Optical science meets visual art / Disruption versus dazzle / Chicanery and conspicuousness / Under the big top at Sims' circus

Wednesday, May 8, 2019

Stinemetz Knew Stieglitz | WWI Ship Camouflage

|

| Alfred Stieglitz, Hands of Helen Freeman (c1920) |

Morgan Stinemetz…is our Art Editor. During the war, he was in the camouflage service of the navy. It is he who will judge the results of the drawing contests, so look out for him!

So who was Morgan Stinemetz? In addition to that page in Everyland, I've found two other sources. One is a multi-page article by Louise Davis, titled ARTIST'S RETREAT: Morgan Stinemetz, who dropped an illustrator's career to become Methodist Publishing House art editor, is a man who finds joy in country life. Published in The Nashville Tennessean Magazine on September 7, 1952 (pp. 6-7, 18-19), it was illustrated by eight photographs of the artist and his artwork, interwoven with interview excerpts. I also found a newspaper obituary that was featured in the Nashville Tennessean on August 20, 1969 (p. 23). He had died at a nursing home in Nashville two days earlier.

Stinemetz was born in Washington DC in 1886. His grandfather, Major Thomas P. Morgan, was one of the first DC police commissioners. His father-in-law was an important DC publisher. As a child, Stinemetz had been interested in animals, as well as in painting and drawing. He studied at the Corcoran School of Art in DC, the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia with Thomas P. Anshutz, a student and later a colleague of Thomas Eakins.

From Philadelphia, Stinemetz returned to New York, where (these are Louise Davis' words) "cubism and other various other 'isms' that startled the new century were taking a firm hold. He experimented with all of them and had his paintings in numerous shows, including the first International Art Show at the Armory in New York in 1913, when Matisse and Picasso were first shown in this country."

He became interested in the literary excursions of Gertrude Stein, and developed a friendship with Alfred Stieglitz, photographer, gallery owner, and the publisher of Camera Work. In 1916, Stieglitz met the painter Georgia O'Keeffe, and soon after they became a pair. It is interesting to note that in the years just prior to this, O'Keeffe had studied with an art educator (and an advocate of the theories of Arthur Wesley Dow) named Alon Bement, who had been her greatest influence. During World War I, Bement was a major contributor to American ship camouflage.

As for Stinemetz, he soon became disillusioned with Modernism. Quoting Davis, he became "fed up with the artificiality of the whole movement." At gallery openings, when he mingled with those in attendance, "he overheard them 'interpreting' things into his work that he had never thought of. …They analyzed every brush stroke, he said, and he was sick of it. He gave up painting on the spot," and turned instead to a new career as a book and magazine illustrator. In subsequent years, he became a well-known illustrator for a variety of popular magazines, among them Collier's, Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, Outdoor Life, and others. He especially enjoyed animal illustrations, and eventually became well-known for his drawings and prints of Scottie dogs. Over the years, he moved from the East Coast to Cincinnati, then settled in Nashville TN as the art director for the Methodist Publishing House.

The US entered WWI in 1917, and soon after artists, designers and architects were encouraged to use their expertise in the development of wartime camouflage. Stinemetz was one of those who contributed to naval camouflage. The article by Davis states that "he served in the navy, capitalizing on the tricks of cubism to camouflage our ships so that enemy submarines would miscalculate their aim." The obituary simply notes that "he designed camouflage for ships of the US Navy." But he may have remained a civilian, since the Navy and the US Shipping Board worked with both military and civilian artists in designing, testing and painting "dazzle" camouflage patterns on ships, both military and commercial (called merchant ships).

Until these references were found, I had never heard of Morgan Stinemetz, much less about his service as a ship camoufleur, so it may be wise to be skeptical of the claim (stated first in the Davis article, then repeated verbatim in the obituary) that "so effective were his distortions of perspective that a record of his camouflage patterns was filed in various museums." Obviously, if such documents still exist, it would surely be helpful to find them.

Postscript (added May 10, 2019): I was mistaken. I had heard of Morgan Stinemetz. A couple of years ago, I gained access to a list (dated September 26, 1918) of sixty-four artists who had studied ship camouflage in New York with William Andrew Mackay. Stinemetz's name is on that list of American Shipping Board camoufleurs from the Second District. This suggests that Stinemetz was a civilian, and most likely not in the Navy.

Friday, May 3, 2019

Friday, July 25, 2025

that cubist painter has progressed as a camoufleur

Above APPLIED CUBISM in Judge, New York, August 2, 1919 (artist’s signature uncertain, previously published in Le Monde Illustré, Paris)—

“This chap has made progress during the war.”

“What’s he been doing?”

“Camouflage!”

•••

RELATED LINKS

On Max Wertheimer and Pablo Picasso: Gestalt Theory, Cubism and Camouflage

Dazzle Camouflage: What is it and how did it work? / Nature, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Women's Rights, and Camouflage / Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Gestalt, and Camouflage / Optical science meets visual art / Disruption versus dazzle / Chicanery and conspicuousness / Under the big top at Sims' circus

Saturday, March 6, 2010

Camouflage as Futurism

In a typically cryptic statement, Marinetti contended that the Vorticists had appropriated Futurist motifs, without attribution, for use in dazzle camouflage. Here is an excerpt from that text in Marinetti's "Aggressive Noisiness and Russolo's Noise Machines" in R.W. Flint, ed., Marinetti: Selected Writings. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972, pp. 335-337—

In London where the English Futurist painters [C.R.W.] Nevinson Wyndham Lewis Wadsworth have distinguished themselves for their proposal to camouflage ships by using dynamic Futurist color patterns by that genius the Roman Futurist Giacomo Balla there took place before and after the concert other furious fistfights and encounters that didn't stop me at all but rather were inspiring as I dared explain even though I didn't know English and pronounced the few phrases I did know badly to the rich and well-educated London that mattered persuading them with gestures that they should respect Luigi Russolo's talent…

Shown above are (left) a plaque on the house of the founder of Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, in Milan, Italy (public domain image); and (right) an Italian Euro coin showing the Futurist sculpture Unique Forms in Continuity of Space by Umberto Boccioni (1913).

Thursday, February 16, 2017

David Linneweh | Compositional Camouflage

|

| Configuration (Rockford) © David Linneweh 2013 • |

In looking at this painting, I am reminded of Wylie Sypher's account (see Rococco to Cubism in Art and Literature) of the constructive-destructive strategies of the cubist designers and painters. These include (as Sypher wrote)—

…a breaking of contours, the passage, so that form merges with the space about it or with other forms, planes or tones that bleed into other planes and tones; outlines that coincide with other outlines, then suddenly reappear in new relations; surfaces that simultaneously recede and advance in relation to other surfaces; parts of objects shifted away, displaced, or changed in tone until forms disappear behind themselves.

Linneweh teaches at the College of Dupage (Glen Ellyn IL), and the College of Lake County (Grayslake IL). He appears to be prolific, as judged by his website, online portfolio, and an interesting series of podcasts called Studio Break. His efforts are well-deserving of an extended, serious look.

• Reproduced by permission of the artist.

Saturday, July 9, 2016

Dazzle: Disguise and Disruption in War and Art

While it is a constant throughout history that conflict has inspired and engendered great art, it is a much rarer event for art to impact directly upon the vicissitudes of war. Yet, in the course of the First World War, a collision of naval strategy and the nascent modern art movement, led to some two thousand British ships going to sea as the largest painted modernist “canvases” in the world covered in abstract, clashing, decorative, and geometric designs in a myriad of colors. Dazzle camouflage had arrived.

Heavily inspired by the Cubism and British Vorticism art movements, dazzle was conceived and developed by celebrated artist and then naval commander Norman Wilkinson. Dazzle camouflage rejects concealment in favor of disruption. It seeks to break up a ship’s silhouette with brightly contrasting geometric designs to make a vessel’s speed and direction incredibly difficult to discern. False painted bow-waves and sterns were used to confuse and throw off the deadly U-boat captains. The high contrast shapes and colors further made it very difficult to match up a ship in the two halves of an optical naval rangefinder. This new book traces the development of the dazzle aesthetic from theory into practice and beyond.