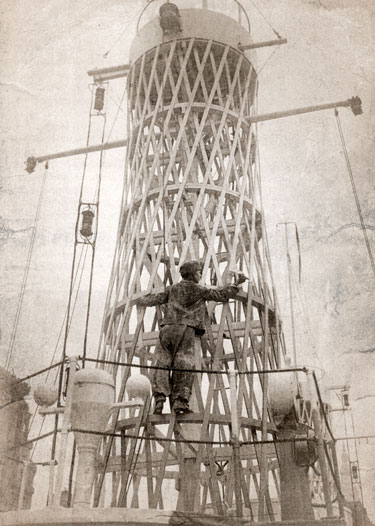

Above Government photograph of an unidentified US Navy Yeoman (F) (or Yeomanette), c1918. Assigned to the Camouflage Section in Washington DC, she is assembling wooden ship models, which were later painted with

camouflage schemes, and tested for effectiveness.

•••

Louise Larned (1890-1972), whose married name was Louise Larned Fasick (she married John E. Fasick in 1929), is sometimes confused with her mother, Louise Alexander Larned (1862-1949). Her father was US Army Colonel Charles William Larned (1850-1911), who briefly served with General George A. Custer in the Seventh Cavalry, but is more commonly known for having taught drawing at West Point Military Academy for 35 years.

Both parents were descended from a long line of military officers, and Louise grew up in the vicinity of West Point. She followed her father’s aptitude for drawing, as well as her family's tradition of serving in the military.

At the beginning of World War I, American women were not allowed to officially serve in the military, but they could provide supporting roles as civilians. In an article in the

New York Tribune,

Anne Furman Goldsmith, the New York chairman of “a proposed camouflage unit of women for service in the United States,” called for women to enroll in the organization. It was planned that they would be trained at a four- to six-week camp by a camouflage expert, and then sail off to duty in France. “There is no age limit for the volunteers,” the article stated, but “they must be physically strong and active, however, and have some knowledge of landscape, mural or scene painting.”

The acceptance of Goldsmith’s proposal was repeatedly delayed (according to the War Department, “it could not spare an instructor”) until the unit was finally established in 1918, with the official title of the

Camouflage Corps of the National League for Women’s Service in New York. Louise Larned volunteered in May of 1918 and joined a group that was taught by artist

H. Ledyard Towle. Joining at the same time was another woman artist, with strong connections to West Point,

Rose Stokes.

After attending the

camouflage camp, the

women camoufleurs (who were sardonically nicknamed “camoufleuses” or “camoufloosies”) took on other projects, most of which used “dazzle” camouflage to attract larger crowds to recruiting and fund-raising events. Overnight, on July 11, 1918, for example, twenty-four of the women camouflage artists painted a multi-colored disruption scheme (using abstract, geometric shapes in black, white, pink, green, and blue) on the

USS Recruit, a wooden recruiting station in Union Square in NYC, built to convincingly look like a ship. Louise Larned and Rose Stokes were members of that painting team.

In September 1918, both Larned and Stokes were assigned to the Navy’s Camouflage Section, where they probably made model ships (to which camouflage was applied for testing) or, as draftsmen, prepared large scale colored diagrams for use by artists at the docks in painting camouflage on the ships.

They had expected to remain on duty until the war’s official end. But the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919, and exactly one month later, newspapers announced that most of the eleven thousand women “yeomanettes” would be discharged early. But certain women were retained, with Larned and Stokes among them. More details were provided by the

Pittsburgh Post:

“Among those who will remain are the artist girls who drew dazzle designs for merchant and battleships—those funny zig-zag stripes which made the Germans waste torpedoes and valuable shells on ships which appeared to be ‘going the wrong way.’ The artists today were working on submarine plans and they like the life.

“‘I do wish the newspapers would say we don’t want to leave the navy,’ said Louise Larned, one of the artistic yeomanettes. ‘We want to be part of the service.’

“And Rose Stokes, whose brothers are all West Pointers, wants to ‘be in the navy—not just a barnacle attached to it by civil service rules.’”

Two months later, a woman journalist named

Edith Moriarty published an article in the

Spokane Chronicle in which she said that, during the war, the government had discovered that women are just as good or better than men at drawing-related tasks, such as drafting charts and diagrams.

She continued:

“Two young women who made good along that line are Miss Rose Stokes of New York and Miss Louise Larned, of West Point NY. These girls, who are both artists, enlisted in the navy as yeomen and they were in New York in the camouflage corps studying to go abroad when the armistice was signed. They have spent most of their time while in the service putting in details on specifications and charts for submarines. The girls are so satisfactory at their work that they have been retained by the navy although many of the yeomen have been relieved of further duty.”

It has so far proved a challenge to locate more specific facts about the life of Louise Larned Fasick. One additional finding is that she was the designer of what was known as the “Navy Girl Poster,” which was presumably used to recruit women to serve in the navy.

•••

Update (August 29, 2019) Sorry, haven't yet located an image file for Louise Larned's poster (there are well-known posters by that tag but they appear to have been the work of

Howard Chandler Christy). However, we have located three paintings by Louise Larned and one by Rose Stokes. Of the four, three are government paintings of ships (two by Larned, one by Stokes), in public domain, and the fourth is a pastel cover painting for

St. Nicholas Magazine (by Larned), dated 1929. They are reproduced below.

Above Louise Larned,

Ocean-Going Tug Towing Target Shed (n.d.)

Above Louise Larned,

Ship of the Nevada Class (n.d.)

Above Rose Stokes,

South Dakota Class Battleship, Concept Drawing (n.d.) [at a cursory glance from a distance, it looks almost identical to the previous Larned painting]

Above Louise Larned, Cover painting for the September 1929 issue of

St. Nicholas Magazine.

•••

Sources

Women Artists Asked For Camouflage Unit: Miss Anne F. Goldsmith Wants One Hundred To Train for Service in France. New York Tribune, October 24, 1917.

Camouflage the Recruit: Woman’s Service Corps Redecorate the Landship in Union Square. Washington Post, May 14, 1918.

Yeomen Rejoice; End of Jobs’ Scorn Is Sighted as Yeomanettes Leave Navy; Girls Establish Good Record. Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh PA), July 28, 1919.

Edith Moriarty, With the Women of Today. Spokane Chronicle (Spokane WA), September 18, 1919.

Roy R. Behrens, ed., Ship Shape: A Dazzle Camouflage Sourcebook. Dysart IA: Bobolink Books, 2012.

•••

Earlier, I had posted a newspaper photograph of Louise Larned and Rose Stokes (

NY Tribune, August 7, 1919) at work drafting plans for submarines. But the picture quality was so poor that I decided to remove it. Nevertheless, the caption for the photograph may still be of interest. It reads:

These girls drew submarine plans for the US Navy instead of knitting socks during the war. They enlisted in the navy as yeomen and were in the camouflage corps in New York studying to go abroad when the armistice was signed. Both girls are artists and will be retained by the navy after yeomanettes are relieved. Miss Rose Stokes of New York City is commander of the Betsy Ross Chapter of the American Legion…

Note A somewhat different version of this post has also been provided to AskART.com.