|

Walter K. Pleuthner at age 82

|

|

Walter Pleuthner's WWI ship camouflage scheme

|

When

Walter Karl Pleuthner registered for the draft in White Plains NY on September 12, 1918, he was officially listed—and signed the verification—as Walter Charles Pleuthner. That’s odd. Elsewhere, I’ve seen him listed as Walter Carl Pleuthner. There is no reason to assume that these were different people, because his birthdate is cited correctly as January 24, 1885. He was 33 years old at the time of his draft registration, and was self-employed as an artist and architect, living on Scarsdale Avenue, in Scarsdale NY.

Pleuthner was born in Buffalo NY. When as young as five years old, he began to take art lessons at what is now the

Buffalo AKG Art Museum. His watercolors were first exhibited in New York City in 1903. Three years later he moved to New York, where he worked in his uncle’s law firm, while taking art courses at the

Art Students League and the

Academy of Design. Among the instructors he studied with were

Frank DuMond and

F. Luis Mora. When the

Armory Show (the infamous International Exhibition of Modern Art) took place in New York in 1913, he was the youngest artist to have his work included.

Later, as an architect, he was primarily known for designing homes for wealthy clients. In 1909, he married

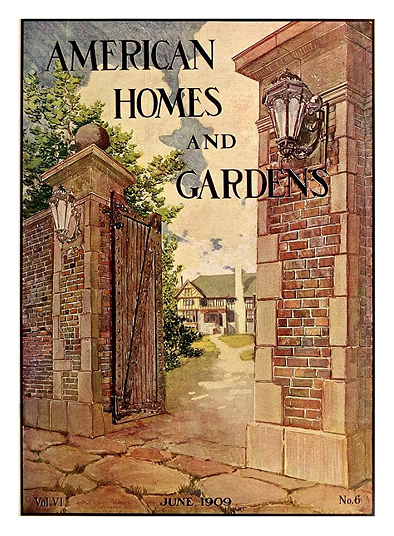

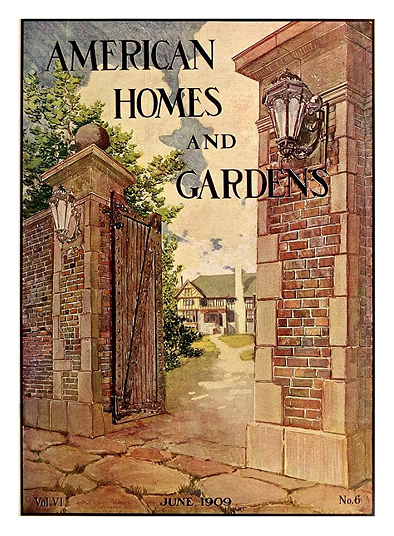

Clara Riopel Von Bott, a concert singer, and designed a spacious stately Tudor home for them in Scarsdale. It was of sufficient distinction that his full color painting of the property’s entrance gate, with a view of the home in the background, was featured on the cover of a 1909 issue of

American Homes and Gardens magazine. In the magazine’s interior pages was a full page feature on the home, with exterior photographs, floor plans, and marginal notes.

|

Magazine Cover / Walter Pleuther / 1909

|

|

Magazine interior featuring Pleuthner home / 1909

|

Pleuthner is listed as having been a member of the

Society of Independent Artists, as well as of a New York group called

American Camouflage, organized by

Barry Faulkner and

Sherry Edmundson Fry (for the purpose of becoming proficient at army camouflage) in anticipation of the US declaration of war in 1917.

At some point, as a civilian, he also became involved in ship camouflage. We know this because there is a photograph of a painted wooden ship silhouette, credited to him, that was published in March 1918 (in black and white only) as part of a lengthy research report by the

Submarine Defense Association. After his scheme was tested by camouflage researchers at

Eastman Kodak Laboratories in Rochester NY, his camouflage proposal was not selected for actual use.

Pleuthner’s wife died from a heart ailment in 1957. He lived for thirteen additional years. His newspaper obituary reads: “His techniques ranged from American impressionism to the unusual use of found objects. He wrote humorous anecdotes and philosophical essays. An architect by profession, he created many of the Gothic and Tudor style homes in Scarsdale and neighboring towns.” He died on December 2, 1970.

The Pleuthners had no children. After his wife’s death, he continued to live alone in their large residence in Scarsdale (although it isn’t entirely clear if this was the original house from 1909, or perhaps a later equivalent from 1920). What is certain is that he had difficulty in maintaining the house. In 1963, it caught on fire, but was not structurally damaged. Soon after, it caught on fire on two other occasions, followed by vandalism and thefts. Concerns were increasingly voiced by area residents, fire safety officials and the village board. Some people urged that the house be condemned and dismantled “as a danger.” This debate provoked a longtime Pleuthner friend and former neighbor to publish an objection in the Scarsdale Inquirer on November 22, 1967.

“We all know Walter’s eccentricities,” the letter to the editor said, “and it is easy to criticize them. With less formal education than some, Walter, through his own efforts, became an excellent architect. He built expensive and admirable houses as far away as Pennsylvania and several in Westchester County…”

The request to raze the Pluethner’s home should be denied, the writer urged. “Walter has suffered several serious misfortunes and since Mrs. Pleuthner’s death, he has mostly lived alone with his paintings and sculpture. His house has suffered damage from fires but appears structurally sound. He is now an old man.”

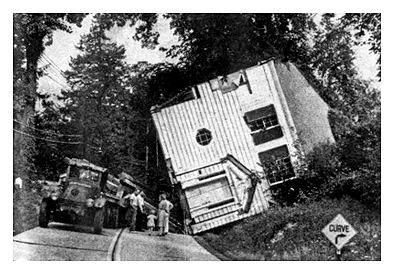

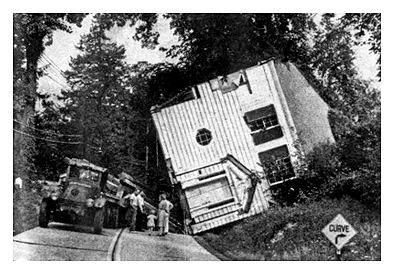

One cannot help but wonder why Pleuthner was regarded as “eccentric,” even among his defenders and friends. One early indication may be a 1941 news article titled “Tipsy House” in the American Builder magazine.

|

Tipsy House: No hurricane; just a bad spill

|

Pleuthner ran into unforessen difficulties, the article reported, “with a model house he bought, cut into two sections and tried to move to another site. After a lot of figuring, he started out at dawn one morning with the first section on a big trailer. Things went all right until they rounded a sharp curve on a hill. At that point the house got tipsy, rolled off the trailer and landed on its side. The house wasn’t damaged, but it got Architect Pleuthner into all sorts of trouble with various people, including the Traffic Department, who objected to having a main highway blocked. Thousands of people who had inspected the house [earlier] when it was known as the ‘Home for Better Living,’ sponsored by Westchester Lighting Company, were intrigued by the sight ot the house, complete with shutters, slate roof and equipment, laying on its side by the road, where it stayed for several days.”

But the straw that eventually broke the authorities’ back was the increasingly disheveled state of his large self-built Tudor home. At the time he built the house, we are told in an article in Progressive Architecture magazine, it “was no more pixyish than many another in the high Eclectic period, and was distinguished only by having true half-timber construction, a massive braced frame with brick nogging. Loving handmade things and solid workmanship, he had the house put together by craftsmen who used a minimal amount of millwork and ready-sawn lumber. One of the timbers in the living room is a heavy stick from the privateer Hornet of War of 1812 fame. Originally, the house reflected in a conventional way Pleuthner’s triple artistic role as architect, painter…and sculptor, as fragments of old ironwork and woodwork and paintings accumulated on the walls. The great living room was the rehearsal room of the Wayside Players, an amateur group that included Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, and the cartoonist Rollin Kirby. At some point, the cultured clutter to be expected in an artist’s house passed over into whimsy, and Pleuthner decided to work on the walls, ceilings, floors, and furnishings of the various interiors. The kitchen at one period was transformed into an Italian garden. Floorboards were painted to imitate polychromed tiles. Other floors were carved out and inlaid with mosaic. A bathroom scale had the outlines of two feet painted on the platform, while the dial became a screaming baby face. Unpleasant book bindings were painted white, with code words daubed on the spines in red. An automobile hood became a canopy over the entrance to a summer house. And more and more odds and ends were added inside and out. In 1963, the house caught fire, but its substantial construction saved it. …the house is now in sad shape. The authorities claim that it is unsafe, and want to tear it down, but Pleuthner is confident that he can restore it. This winter, the house was leaky, drafty, and uninhabitable, but Pleuthner is already experimenting with the textural effects created on the floor by the latest fire.”

|

Pleuthner home interior in 1968

|

When that article appeared in 1968, Walter Pleuthner was 82 years old. His home was condemned and soon after demolished near the end of that year. When he died two years later, he was listed as residing at a nursing home in White Plains.

SOURCES

• Cover and “A Handmade House, Walter Pleuthner, Architect,” in American Homes and Gardens. Vol IV No 6, June 1909, p. 78.

• “Tipsy House” in American Builder 1941-09: Vol 63 Issue 9, p. 87.

• Letters to the Editor, Harold A. Herriet, “Defends Walter Pleuthner” in Scarsdale Inquirer, Vol XLIV No 47, November 22, 1967.

• “Dwellings: The Rationales in their Design” in Progressive Architecture, May 1968.

• “Walter K. Pleuthner” [obituary], in Scarsdale Inquirer. Vol 52 No 49, December 10, 1970.