|

| free online video / full view |

Sunday, December 25, 2022

Friday, December 23, 2022

deceptive non-service in the WWII camouflage corps

•••

Lee Hall, Wallace Herndon Smith: paintings. University of Washington Press, 1987, pp. 60 and 64—

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, the Smiths were entertaining friends at lunch in their comfortable home in the country. A neighbor who had not been included in the party rushed in shouting, “Turn on the radio, turn on the radio.” Conversation stopped and while the guests tried to make sense of the neighbor’s urgent cries, he added, “They’re bombing us.” The Smiths and their guests, knowing the interloper’s proclivities for alcohol, assumed that he was well under the influence. When the message bearer dived under the piano, still wailing, they were prepared to dismiss his cries as an inept joke among joking neighbors. Soon, however, they were persuaded to tune in the radio and, with millions of other Americans, they learned of Pearl Harbor.

Talk of war—of Hitler and Europe, of England and of the United States’ loyalties—hummed in Connecticut as elsewhere. But even so, the news of the Japanese attack staggered the revellers. The next morning Wally telephoned a friend from Princeton who lived in Washington and who, to Wally's vague recollection, worked for the government. Through this friend, Wally managed to make an appointment with yet another friend who, he believed, "was handing out commissions." He flew to Washington and returned to Connecticut as a captain in the Camouflage Corps. “I was given a costume [a uniform],” he said, “but I never wore it.”…

The Camouflage Corps, to which Wally had been assigned as a commissioned officer, was by this time stationed in Missouri. Captain Smith was not called up to serve, but he chose nonetheless to mingle from time to time with his fellow officers. “The Camouflage Corps,” according to Kelse [Smith, his wife], “was a joke. They fought the war in the bars of the Chase and Park Plaza hotels.”

restaurant robbery and a camouflaged futurist coffin

•••

REDSKINS GET $1,000 LOOT. Brooklyn Gunmen Paint Faces Then Stage Holdup. East Liverpool Review. East Liverpool OH, July 16, 1928, p. 8—

NEW YORK, July I6—Chicago gunmen may claim the distinction of having first introduced the submachine gun into the hold-up “racket,” but to Brooklyn goes credit for the first use of camouflage by stick up men. Three bandits today entered a State Street restaurant with their faces disguised with paint used in a manner like that employed formerly only by Indians on the warpath. The paint was streaked over their faces in [a] weird pattern. The leader wore a heavy black hue under one eye, while the rest of his face was streaked a brilliant red. The proprietor and his staff were so astonished that the bandits escaped with $1,000 in cash and jewelry before an alarm was raised.

RELATED LINKS

Dazzle Camouflage: What is it and how did it work? / Nature, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Women's Rights, and Camouflage / Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Gestalt, and Camouflage / Optical science meets visual art / Disruption versus dazzle / Chicanery and conspicuousness / Under the big top at Sims' circus

Monday, December 12, 2022

Nichols brothers / NY ship camoufleurs during WWI

|

| Hobart Nichols |

His brother (pictured below) was also an accomplished artist, Spencer Baird Nichols (1875-1950). Both resided in Lawrence Park, an artists’ colony near Bronxville NY. His brother was also a civilian ship camoufleur, both of them being affiliated with the Marine Camoufleurs of the US Shipping Board, Second District, a section that was headed by William Andrew MacKay.

•••

MR. HOBART NICHOLS TALKS TO NONDESCRIPT CLUB

Bronxville Review (Bronxville NY) April 11, 1919, p. 1—

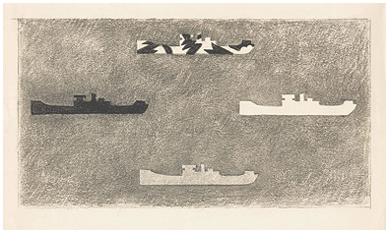

Mr. Hobart Nichols [American illustrator and landscape painter] of this village talked most entertainingly to the ladies of the Nondescript Club, at the regular weekly meeting on Tuesday, on the subject of camouflage. Mr. Nichols was connected with the camouflage department of the United States Navy. He illustrated his remarks by drawings of his own, and by various miniature camouflaged ships. He made it quite clear how the effects produced render good aim at a camouflaged vessel most impossible. The remarkable showing of less than one per cent of ships sunk, demonstrated the value of the work.

|

| Spencer Nichols |

Saturday, December 10, 2022

correction of misattribution of magazine cover image

So at last the mystery has been solved. In September 2017, we blogged about an illustration of a dazzle-camouflaged ship that was published on the cover of the December 1918 issue of Sunset: The Pacific Monthly. It's quite a stunning image, and the magazine lists the artist as Harold von Schmidt, which we at first accepted as fact. But we began to have second thoughts, because if you look closely at the lower left corner, the artist has signed the painting as "Bull," not "von Schmidt." So, in the earlier post, we listed the names of both artists.

As of yesterday, we have resolved the misattribution. The magazine was in error when it listed Von Schmidt as the artist. Instead it was the work of Charles Livingston Bull (1874-1932). In the process of reading the text of a von Schmidt exhibition catalog (John M. Carroll, Von Schmidt: The Complete Illustrator. Fort Collins CO: Old Army Press, 1973), we ran across the following note—

"Sunset Magazine December 1918, Cover: 'His Imperial Majesty's Peace Ship Camouflage!' (This picture is in dispute. Although the artist claims he did not do the painting, the magazine issue gives him credit for having done it.)"

Thursday, December 8, 2022

Peanut Prieto selects a Chandler Coupe closed car

|

| Humorist Kayem Grier (1920) |

According to the news story accompanying the photograph, the Salt Lake City native was “not only a humorous writer. He is one of the most experienced motorists in the state…[Earlier] he became widely known to thousands of followers of the auto racing game throughout the middle west. In 1914, he toured the middle west with a racing car, driving half-mile tracks and thrilling thousands of visitors at state and county fairs in a series of sensational races. In the process, he was the owner of twenty-nine different kinds of cars. The article announces that he had selected a Chandler coupe “as his ultimate choice of an automobile.” The photograph was published in the Deseret News (Salt Lake City UT), May 29, 1920, p. iv., with the headline Peanut Pietro Selects Chandler Closed Car.

•••

Kayem Grier [Kenneth M. Grier], PEANUT PIETRO, in Irvingville Gazette, November 19, 1920—

Other day I toll thy boss bouta somating wot I tink. And he say to me you no better speaka dat way out loud eef you lika to stay een deesa place longa time. He say, "Eet you roasta ladies, Pietro, ees alla same keeka dirt on your own grave."

But wot he tella me ees no scare ver mooch. Eef I lika somating I like plenta mooch and eef I no lika I gotta deesgust. So I speaka wot I tink eef ees breaka my neck, I no care. When da war broka out somebody eenvent camouflage for maka every ting looka wot aint. Weeth da camouflage one ship ees looka lika two ship and two ship looka lika no ship. Weeth plenta paint everyting ees made for looka deefrence—jusa for foola other guy.

And now when da war ees queet some da women keepa right on do sama ting. I see one woman other day weeth so moocha paint on could foola U-boat. Eef we use so' moocha black powder on da Germans as women use white powder on da face mebbe we gotta heem licked long time ago.

Seema lika only ting some cheecken do now ees scrubba da nose white, paint da cheek peenk, maka red lips and putta google een da eye weeth black stick. Lika data way da face stick out lika sore thumb. And when ees come on da street she maka more noise as da dire engine.

One girl tella me she jusa putta nough on for stoppa da shine. She gotta so mooch on I feegure mebbe she tink her face ees headlight, dunno. Longa time ago I reada some place dat da pen ees stronga like da sword, or somating. For way some da women looka now I feegare da powder puff ees greater as da wash rog. But dunno—

Wot you tink?

is crime not to be depended upon / who can we trust?

Above A pictorial advertisement for a Victorian-era British illusionist, T[homas] Elder Hearn.

•••

Alas! This is An Age of Ingenious Camouflage, in Salina Journal (Salina KS), January 17, 1920—

New York—This is an age of camouflage. Yes; of course the word has been overworked. Maybe it isn't used any more in our best journalistic circles. But it's an age of camouflage just the same. Now take the case of John Smith of the East end, up for examination in a case of assault and battery. He did not deny that Emil Emilson hired him to beat up Joe Lansky or that he got $5 from Emil for beating up Joe. But he strongly denied that he did beat up Joe. Finally they got the truth out of John, who thus explained the seeming inconsistencies of his statement:

“When a fellow is hired to do up another guy he goes and tells him about it. Then they get together and they stick court plaster all over the guy's face and tie a bandage around his head with a little beef blood showing through and put his arm in a sling. The guy who wants him done up looks him over and thinks he got his money's worth.”

Now this is art, but is it honest? Is crime not to be depended upon to be what it seems? We know that our leather chairs are not made of hide, but of old rubber boots and condensed milk. We know that chicken salad is frequently made of veal. We understand that our sealskin coats are made from the fur of the muskrat and that our linen is cotton. Knowing, nobody cares. But it had been supposed that crime was above substitution. Here we have a detailed description of camouflage assault.

When thugs become too ingenious to kick in the ribs of the persons they are paid to assault and resort to camouflage to make the patron think he is getting something just as good, whither are we drifting?

Monday, December 5, 2022

Camouflage Cartoons Archive online at ScholarWorks

|

| Online Camouflage Cartoons Archive |

Wednesday, November 23, 2022

hidden horse / caw said crows are calling his name

vintage picture puzzle / harmless sleeping puppy dog

Beginning at the top, the first two images are somewhat suggestive (not unlike an inkblot) but require some work to interpret. The third one is more likely to be seen as a human face, albeit greatly distorted.

But the puzzle is solved at the bottom, when a closer look reveals that all four have resulted from a single photograph of a harmless sleeping puppy dog. For more on embedded figures and picture puzzles, see this brief video, articles on Clemens Gretter, Gobolinks, and camouflage.

Sunday, November 20, 2022

ScholarWorks / American Women Camouflage Exhibit

|

| UNI ScholarWorks Exhibit |

The exhibition, consisting of forty vintage photographs, and titled HIDDEN FIGURES, premiered in a multiple-month exhibit at the Betty Strong Encounter Center and Sioux City Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center, in Sioux City IA.

The photographs in the exhibition, supplemented by text captions, have recently been posted on the ScholarWorks website of the Rod Library at the University of Northern Iowa.

The activities of these women camoufleurs, as well as their connections to the Womens’ Suffrage Movement, are also featured in a recently completed documentary video (free here online), called Art, Women’s Rights, and Camouflage, and in a scholarly essay titled Chicanery and Conspicuousness: Social Repercussions of World War I Ship Camouflage (available online also).

WWI French camouflage cartoons by André Hellé

Above A page of camouflage-related comic drawings by World War I French illustrator and toy designer André Hellé, as published in La Baïonnette, c1916.

La Baïonnette

•••

Jerrold A. Morris, 100 Years of Canadian Drawings. New York: Methuen, 1980, p. 10—

The lover of drawings has the advantage of being in close contact with the artist’s original concept conveyed in a relatively uncomplicated medium. Drawing, in the widest sense of the term, is the linear element in art least susceptible to manipulation by what [William] Blake called “Blotting” and the Pre-Raphaelites called “Slosh”—we might call it “fudging.” Among painters are many masters of camouflage, what [J.A.D.] Ingres meant when he said that drawing is “the probity of art.”

Saturday, November 19, 2022

Camoufleur John Wilde in Walter SH Hamady's books

Above Page spread from Reeve Lindberg, John's Apples (Perishable Press, 1995), a Walter Hamady letterpress book, with full-color paintings of apples by John Wilde [WILL-dee].

•••

John Wilde: Recent Work, April 10-May 3, 2003. New York: Spanierman Gallery, 2003, p. 4—

His [Wilde’s] art interests developed early, as he recalled in 1986: “I have always loved to draw and paint ever since junior high school in Milwaukee. I was particularly fond of drawing imaginary cities, which I then erased and re-created.” In 1938 Wilde enrolled in the art department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he studied human anatomy with Roland Stebbins and drawing with American Scene painter James Watrous. Shortly after he graduated, in 1942, Wilde was drafted into the army and served four years drawing camouflage and modeling terrain maps for various units (including the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS [precursor to the CIA]), while also meticulously detailing his disgust and dismay with wartime in a 275-page sketchbook.

•••

Below Page spread from Walter Hamady and John Wilde, A Hamady Wilde Sampler / Salutations 1995 (Perishable Press, 2001), including a self-portrait drawing by Wilde, presumably painting an apple. And below that, Roy R. Behrens, Mon Dieu. Collage in open-book form (1993). Hamady Collection.

|

| Roy R. Behrens (1993) |

Friday, November 18, 2022

Canadian camouflage artist Rowley Walter Murphy

Above Dazzle-camouflaged transport ship (AI colorized), 1942.

•••

Mary El Cane, "Staff and Nonsense" column, in Sketch (Ontario College of Art), February 27, 1947, p. 1—

Meet the Navy, in the person of Rowley [Walter] Murphy [1891-1975]. Many years of yachting since 1898, he insists readied him for full wartime effort on destroyers corvettes, ad infinitum. Canaling was a specialty with him, and also a possible excuse for some sketching of masters and mates of the tugs and freighters on the Welland Canal. He spent some time sailing the pilot schooner off Halifax harbor, swishing around in a relation of the Bluenose. Admiral Jones kept him busy for a time on the designing of naval camouflage, a job more exacting than people realize. (“Karl, vos is das on dur distance an iceberger?” “Yah, Hermann, idz torpedering us! Mervy doned id agen!”)

Monday, November 14, 2022

a modern bus like noah's ark with 12 pygmies inside

|

| Tudor Hart's WWI tank camouflage |

•••

Ilya Ehrenburg, People and Life: memoirs of 1891-1917. London: MacGibbon and Kee, 1961, p. 184—

Here is how in 1916, I described the first tank I had seen: “There is about it something majestic and nauseating. It may be that once there existed a breed of gigantic insects; the tank is like them. It has been brightly decorated for camouflage; the flanks resemble the paintings of the Futurists. It creeps along slowly, like a caterpillar; trenches, bushes, barbed wire, nothing can stop it. Its feelers twitch: they are guns and machine guns. In it, the archaic is combined with the ultra-American, Noah’s Ark with a twenty-first century bus. Inside there are men, twelve pygmies, who innocently believe that they are the tank’s masters.”

Thursday, November 10, 2022

she was not only good in math, science & philosophy

|

| Frida Kahlo |

“Everyone said I had an eye for color,” she told me, very impressed with herself. “Only that stupid Lorenzo, you know what he said? He said I should become a dress designer!” Obviously, she thought dress designing was beneath her, although as an adult she actually wore a lot of her own creations. I can understand how someone might have thought that Frida would become a dress designer. She was so particular about her clothes—the jewelry, the colors, the ribbons in her hair. Everything had to match. Clever Frida. I have to admit it; she was good not only in math and science and philosophy, but she knew how to doll herself up in order to camouflage her defects. I mean, Frida wasn’t really pretty—I told you that before—but she was very particular about her appearance. She took hours to get dressed and do her hair. It was important to her to divert people’s eyes from that ugly, deformed leg. More>>>

amazing how war finds use for anything—even artists

Gerard Woodward, Vanishing. London: Picador, 2014, p. 466—

Shortly after this, back at the barracks, I was called in to see the major. He said the following: "I've had a request for your transfer, Private Brill. It seems someone somewhere in the higher echelons of command thinks you might have a use. The army is forming a Camouflage Corps, and they have specifically asked for you to be part of it. How does it feel to be loved, eh? Well, I suppose they're looking for anyone with artistic credentials. You used to be an art teacher, didn't you? Amazing, isn't it, how war finds use for anything, even artists? Here's your travel warrant. You'll be leaving tomorrow."

Monday, November 7, 2022

landscape camouflage as flat pattern abstract design

Above Collier’s: The National Weekly. January 10, 1914. Artist unknown. This cover design and illustration do not pertain directly to Louis B. Siegriest or military camouflage. But the jacket the person is wearing, with its “flat pattern” abstract design, seems entirely consistent.

•••

Louis Siegriest in Louis Bassi Siegriest Reminiscences: Oral History Transcript. Interview conducted by V.L. Gilb. California: Bancroft Library, 1954—

[At the time that the US entered World War II in 1941]…I knew a man [in San Francisco] who had been in the First World War as a camoufleur. He called me up and asked me if I would like to come down and join the camouflage outfit. So I thought that would be a thing I would want to do, and I went down and joined the camouflage outfit.

…This was with the US Engineers [Army Corps of Engineers]. That was I think the third day after the war [was declared]…

…they were looking for camoufleurs at that time, and they were very hard to get because very few people had experience, which I myself didn’t have, but this man, he was in the First World War [in France], and he was with [Homer] St. Gaudens and Abe Rattner, the painter.

…So he sort of took charge of the training of the men to be camoufleurs because the men who were head[ing] the department knew nothing of it. They had to read all this time while this fellow took over and trained us to do this type of work.

…His name was Stanley Long [1892-1972]. He is an artist, himself. He has a show at the present time [1954] at the Maxwell Gallery of cowboys and horses. He’s pretty good at it, too, Western type of painting…

…I stayed with them [the camouflage unit] until practically the end of the war…

[Question: How did your work at a WWII camoufleur contribute to your eventual work as an abstract painter?]

…Well, all this time we were working on the drawings of camouflage installations, [and] it had to be worked out in flat pattern. And they all worked into sort of abstract patterns, and that sort of interested me because I had never worked that way. But I had a feeling all the time that that was something I would like to do. So it sort of changed my painting, after working in this camouflage work. I saw things with a different view than I had before. And I still don’t paint as an abstract [artist], but I use an abstract pattern as a base in practically everything I do. I mean I start that way, in more or less flat pattern. And then I work my realistic [components] into the pattern. I found that it works out better than the way I used to work, just straight painting and trying to pull it all together. This way I start out with a pattern, and I worked into it that way.

•••

In a later interview, conducted in 1978 for the Archives of American Art by Terry St. John and Paul Karlstrom, Siegriest gave a slightly different account of the same experiences:

Question: …Some time in 1941 you went to work for the United States Army Corps of Engineers. What did you do for them?

LS: I went into camouflage at that time. There was that cowboy artist by the name of Danny Long [sic, Stanley Long], whom I knew. He was a friend of [Maurice] Logan’s. I met him over in San Francisco on the second day of the war, I think. He said they had just called him back. He did camouflage during the First World War, and he said they called him back to teach the younger fellows camouflage. He said, “Why don’t you join up?” I said I would love to. It took me a couple of days to go through the process, but I finally went in and it was easy for me. You were assigned to a job and you made these designs and then they were handed out to different companies to do the work.

Q: Now you did a design like a flat abstract pattern. Would it be an aerial view?

LS: An aerial view.

Q: And then your design would be sent out to...

LS: Different companies. They would do the painting, nets or whatever.

Q: What was it like over at Fort Cronkite and around there? Didn’t they use different colored plants and things like that to create patterns?

LS: Yes, but I did the Benicia thing up there, Benicia arsenals. That was designed mostly in there and I wouldn’t have a great deal to do. I’d look at how it looked and then I would fly it.

Q: They’d put you in an airplane?

LS: Yes, I’d go to Hamilton Field, get a plane and go up there. At 6,000 feet I’d look at it.

Q: How did it look?

LS: It was okay, sometimes I’d change the design.

Q: What did it look like at 10,000 feet?

LS: It looked like an abstract design. The way I did it was to go up there first and see what the land looked like on the outside. Then I’d bring the land in to the buildings; if there was a green patch over there I’d bring the green patch into the buildings. If there was brown, or dark, I’d bring it all in. So I’d go up and look down and see if that was right. And then there were other ways of doing it. I went up to Klamath, which was a radar station, and bought an old barn and moved it down (the barn) over the top of the radar station. We were on the coast.

Q: How did it look?

LS: Oh, it looked like a ranch, I’d build fences all around.

Q: What was your experience as an artist?… Did this turn you on to any ideas for your later paintings?

LS: Well, more or less, I guess it did. At that time I painted. I even took my paints along.

Q: What kind of paintings did you do?

LS: I’d do things along the coast, you know.

Q: More straightforward kind of landscapes?

LS: More straightforward landscapes.

Q: Previously when you were doing landscapes you were looking straight ahead at them, and that’s a very abstract way of looking at landscape, like looking down.

LS: I even painted some of the installations. I got into a lot of trouble by doing it because the Army thought I was giving secrets away. They took all the paintings from me and locked them up. I got them back. Well, that was good, working for the camouflage. And then, during that time, Life and Time had war artists.…

Postscript It may also be of interest that Louis Siegriest's second wife, artist Edna Stoddart (1888-1966), née Edna Lehnhardt, was the niece of Josephine Earp, the common-law wife of Wyatt Earp.

Ding Cong / camouflaged wit and humor from china

Above is his illustration of the following traditional story, as told by Chinese artist Ding Cong (who signed his work as Xiao Ding) (1916-2009).

•••

Ding Cong, Wit and Humor from Ancient China: One Hundred Cartoons. China Books and Periodicals, 1986—

92. Camouflage with Leaves—

A poor man from the state of Chu once read the following in a book: “A mantis camouflaged itself while waiting to pounce on a cicada.” The man then gathered some leaves under a tree and used them to camouflage himself. When he asked his wife if she could identify him she spoke truthfully and said, “Yes, I can.” The man then changed his posture and asked her several more times. Becoming annoyed by this practice, she finally told him that she was unable to identify him. The man was very glad.

Thus camouflaged with leaves the man went to the market and stole things from the open stalls. But he was caught and summoned to the magistrate’s court. After the man confessed, the magistrate burst into laughter and set him free. He found the man’s conduct so inane that he decided not to punish him.

Thursday, November 3, 2022

WWII charming camouflage fashions for mothers to be

The [World War II British] camouflage soldiers were, on the whole, the most unwarlike collection of men imaginable—painters, sculptors, designers, and architects. They had, in fact, been drawn from the very section of the community that, in warfare, the regular soldier regarded as a bit of a joke.…

An example of the regular army’s attitude in dealing with the camouflage men…was described by Geoffrey Barkas in an article written in 1952 for the Royal Army Ordnance Corps Gazette. Barkas, as chief camouflage officer, Middle East Forces, had been informed that an expeditionary force was being assembled under the code name Lustre Force and that he was to be responsible for its camouflage equipment. He asked where Lustre Force was going, but for reasons of security such information could on no account be divulged. Could he have some clue on suitable tones and colors—was it a yellow, brown, or green country, lumpy or flat, with trees or none? Certainly not. That would be telling him where Lustre Force was going. What was the size and composition of the force, and how long did he have to assemble the material? But this was expecting the planners to reveal the date of embarkation! Barkas did, eventually, make an accurate guess (the destination was Greece) and by direct approach to the director of Ordnance Services he got the support he needed. Although only a few weeks remained for assembling the camouflage supplies, Lustre Force was equipped.

Tuesday, November 1, 2022

disruptive geezer theatre doors / wartime propaganda

It was common at the time for "scenic artists" (theatre and film set designers) to be assigned to wartime camouflage.

The treatment of this entrance was a way of promoting the screening of a 1918 short propaganda film titled The Geezer of Berlin, which was of course in reference to the German Kaiser, aka the Beast of Berlin, and the Clown Prince (in reference to his son). Disruptive patterns such as these not only cause visual confusion; they can also disturb the emotions, and, to some extent, designs like this anticipate the use of skewed perspective and shape deformation in avant-garde "expressionist" films, such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a recent video, titled Ames and Anamorphosis, I have talked about the use of distorted perspective in that and other early films.

Sunday, October 30, 2022

camouflage pattern on armored truck in world war one

We have regrettably misplaced the source for this vintage wartime photograph. My best recall is that it is a camouflaged World War I armored truck (almost a hyrid tank of sorts) from Northern Europe, with AI colorization.

RELATED LINKS

Dazzle Camouflage: What is it and how did it work? / Nature, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Women's Rights, and Camouflage / Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage / Art, Gestalt, and Camouflage / Optical science meets visual art / Disruption versus dazzle / Chicanery and conspicuousness / Under the big top at Sims' circus

Abbott Thayer and Concealing Coloration / Dublin NH

Above Abbott Handerson Thayer, Charcoal drawing for ship camouflage experiment, c1915. From Abbott Handerson Thayer Family Collection.

•••

Excerpted from L.W. Leonard and J.L. Seward, The History of Dublin NH. Published by the Town of Dublin, 1920, pp. 684-686—

Throughout the world the word “camouflage” has become familiar during the war. Although this word is of French origin, the thing itself is primarily an American creation, the work neither of warriors nor army experts, but of a distinguished artist, a well-known Dublin resident, Abbott H. Thayer, who has permanently lived here for more than twenty-five years.

In 1896, an essay by Mr. Thayer on “The Law Which Underlies Protective Coloration,” was published in The Auk, and shortly afterwards reprinted in the Year Book of the Smithsonian Institution. In 1909, the Macmillans published Concealing-coloration in the Animal Kingdom, written by Abbott H. Thayer’s son, Gerald H. Thayer, and illustrated by father and son.

Protective coloration, as set forth in this book, was one of the main starting points of camouflage, and to a considerable extent has guided its development. Assurance of these facts were given Mr. Thayer in England and Scotland in the winter of 1915-16, when he went abroad to tender the Allies’ more direct help in this matter.

Professor [Sir William Abbott] Herdman of the University of Liverpool, suggested that the naturalists of Great Britain ought to sign a joint statement to the effect that they believed Mr. Thayer’s unique knowledge of protective coloration could be made of the greatest use to the War Department. It proved, however, that, owing to the efforts of several other British scientists, notably Professor J. Graham Kerr of Cambridge and the University of Glasgow, who had even urged that the government create a special bureau for the adoption of Thayer’s discoveries, “concealing coloration” was already doing war service of various kinds, both on land and sea.

Camouflage has carried the principles of visual deception to hitherto undreamed-of lengths of application, and to manifold and divergent new developments.

But the latest military camouflage was mainly a matter of masking batteries and guns for airplane detection. Standardized materials, wire netting, colored shreds of burlap, etc., manufactured in vast quantities behind the lines were the main dependence for this roofing-over and screening of guns. The latest marine camouflage, again, sought not concealment of ships, but effects of distortion of outline and perspective which would puzzle the U-boat observers looking through the periscope, as to the vessel’s speed, distance, exact form, and especially her course, or direction of movement.

Professor E. B. Poulton, F. R. S., etc., President of the Linnean Society of London, the distinguished English evolutionist, writes as follows:

“During the sixty years which have elapsed since the historic day [of the reading before the Linnean Society of Darwin’s and Wallace’s joint essay on Natural Selection], English-speaking workers—among the foremost the American artist-naturalist, Abbott H. Thayer, and his son Gerald H. Thayer—have studied this principle [protective coloration], continually extending it by the discovery of fresh applications, and analysing it into a whole group of cooperating principles; but inspite of all these naturalists have done, it required the Great War and a misused French word in order to arrest the attention of their fellow-countrymen…

We may, however, forgive the inccurate use of a new word which the war has bought into our language because of the attention which has now been focused upon a most interesting subject—attention which rightly demands a new and widely accessible edition of this work [Thayers’ Concealing Coloration]. Here are clearly explained and illustrated the principles underlying the art of camouflage, practiced by nature from time immemorial but in some of its main lines only made known to man by the discoveries of Abbott H. Thayer.”

Saturday, October 29, 2022

Thayer's camouflage of William James' Norfolk jacket

Above A comparison of two photographs, the one on the far left identified as Abbott H. Thayer, attired in a Norfolk hunting jacket that had previously been owned by philosopher William James. When James, a friend of Thayer, died, the jacket was given to Thayer by James' two sons, Aleck and Billy, both of whom were artists and had studied with Thayer.

Later, early in World War I, Thayer used that same jacket as a way to demonstrate how fabric scraps (rags) and his wife's discarded stockings might be attached to its surface, to break the continuity of the figure. By superimposing the one photograph on top of the other, I am trying to "prove" that the person in the photograph in the center and on the right (unidentified when published) is in fact Abbott Thayer himself, with a painted face, wearing that Norfolk jacket.

•••

Be warned that the story below is full of inaccuracies. Thayer submitted a ship camouflage proposal (based on countershading) to the US Government during the Spanish-American War (not WWI), but asked for too much money. I have never seen any indication that he was asked, during WWI, “to guide a Navy program.” He did attempt (ineptly) to persuade the British to adopt disruptively patterned infantry uniforms—but his prototype was literally made (as shown above) partly of rags and worn-out womens' hose.

•••

Ernest Henderson, The World of “Mr. Sheraton.” New York: Popular Library, 1962, p. 83—

When World War I was raging, deceptive markings to disguise merchant ships falling prey to German torpedoes became a matter of national necessity. To meet this grave emergency, Dublin’s [NH] great naturalist [artist Abbott H. Thayer] was offered an impressive financial inducement to guide a Navy program for confusing the enemy with camouflage. Despite a threatening spector of poverty, Thayer flatly declined. It would mean a military role, and this his conscience would not then permit.

Subsequently, as the fever of war increased, realizing that human lives were involved, Thayer offered the British a new type of uniform designed to render soldiers partially invisible. This the British promptly rejected, concluding, no doubt, that fitting their men with unbecoming rags could injure national morale even more than could a mere reduction in the deadliness of approaching German bullets.

Abbott Handerson Thayer / the master at his very best

|

| Abbott H. Thayer (c1915) |

•••

Ernest Henderson, The World of “Mr. Sheraton.” New York: Popular Library, 1962, pp. 82-83—

Another Dublin [NH] resident was the artist and naturalist Abbott H. Thayer, considered by many the discoverer of protective coloration. While still in my teens, I saw a demonstration of his skill. He had produced a piece of stone carved to resemble a duck. Painted to match the roadway, the object had a dark brown back, with much lighter colors on its belly.

In broad daylight Thayer placed the duck, supported by a stiff wire, in the roadway and led me twenty paces away. Turning, I was sure the object had vanished; nothing was visible at all. A few paces nearer, and the wire could be seen—absolutely nothing else. Another few paces, and the duck began to take form. Yes, Abbott Thayer had indeed mastered nature’s private secret for deceiving the human eye.

Friday, October 28, 2022

Gerome Brush and his memorial to Edward Thaw Jr.

|

| Kasebier portrait of Evelyn Nesbit (1903) |

•••

Susan Wilson, Garden of Memories: A guide to historic Forest Hills. Boston: Forest Hills Educational Trust, 1998—

As you ascend [Milton Hill at Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston], you’ll see on the left one of the cemetery’s most unsual portrait sculptures. A winged, iron-clad archangel Michael stands by a beautiful young man, resting one hand on the youth’s shoulder, and another on a sword. The monument commemorates aviator Edward Thaw Jr (1908-1934) of Milton, who crashed in the mountains of New Mexico, while piloting a private plane from Quincy to San Diego.

Edward was the nephew of Harry K. Thaw, the millionaire who murdered handsome society architect Stanford White on the roof of Madison Square Garden in 1906. White’s crime was his tempestuous affair with showgirl Evelyn Nesbitt—his “Girl on the Red Velvet Swing”—prior to her marriage to Thaw. Thaw was aquitted on grounds of insanity.

Nephew Edward’s memorial at Forest Hills, commissioned by his mother, Jane Thaw, was sculpted by Gerome Brush. Son of well-known painter George DeForest Brush [and early aviator and airplane camoufleur Mittie Taylor Brush], Gerome studied art as a child in Europe [he was named in honor of French Academy painter, Jean-Leon Gerome, his father’s teacher], and was apprenticed to a Florentine marble carver. Upon returning to America, he worked on the World War I military [ship] camouflage program, and became a respected portraitist and painter, as well as an architectural and memorial sculptor.

•••

Below Roy R. Behrens, Death Announced, digital montage (2021), in which various vintage public domain graphic components have been altered and recombined. In the center background is a digitally-colored photograph of an enshrouded Evelyn Nesbit, being steadied by an assistant, as she appears in public for the first time after the death of Stanford White.

|

| Digital montage © Roy R. Behrens 2021 |

Sunday, October 23, 2022

Abbott Handerson Thayer / family collection website

Also posted is a list of recent Thayer exhibitions, and a free downloadable pdf of the full-color, 68-page exhibition catalog, edited by Ari Post, titled Abbott Handerson Thayer: A Beautiful Law of Nature (2013), which includes three essays, by William Kloss, Martin Stevens, and myself. See also my recent 30-minute video talk on the same subject.

camouflage tricks behind the scenes in hollywood

|

| Boston Globe, June 15, 1921 |

The studio scenic artist of today…is an expert camouflage artist and a perfect copyist. The controlling principal in his work, however, is the photographic value of colors. Under the eye of the camera colors are often very deceptive, and often a color, which seems lighter to the eye than another color, might on the screen register a darker shade of gray than that color.

Often two colors which seem to form a most artistic and beautiful combination to the human eye, will, when photographed, present a most inharmonious, discordant color scheme, which is very ugly to look upon. Only by a careful study and a perfect knowledge of the photographic values of colors does the scenic artist avoid such color clashes.

The art of camouflage also is a very important phase of the studio scene painter’s art. He must make the imitation appear exactly like the real. Some of the commonest of such problems are included in the following examples: The camouflage of compo[sition] board squares and the proper laying of them so that when photographed they resemble a tile or stone floor; the painting of surfaces so that the result photographs like bronze, gold or other metals.

The artist can, with a well-placed strokes of his brush, dipped in the right kind of paint, make a new brick wall like the side of a dingy tenement house. He can give to a new redwood panelled wall the effect of an oak panel, hundreds of years old.

Saturday, October 22, 2022

Frank Bird Masters: ship camoufleur and photographer

In that post, we talked about Maurice L. Freedman (1898-1983), who was a District Camoufleur for the US Shipping Board, assigned to Jacksonville FL. Freedman is of interest because, following the war, when he enrolled as a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, he donated to its library a nearly complete set of the colored lithographic plans for “dazzle camouflage” schemes that were designed by US Navy camoufleurs in Washington DC. That rare collection has survived and remains in the library's archives at RISD in Providence.

In that same post, we also shared information about another Florida-based ship camoufleur named Frank Bird Masters (1873-1955), who was present at the launching in Tampa, and who was apparently in charge of applying the camouflage scheme to the SS Everglades.

More detail is in our original blog post, but it may be sufficient to say that Masters was a magazine and book illustrator who had initially studied science and engineering at MIT, graduating in 1895. A few years later, he changed his profession to that of an illustrator, and studied with well-known artist Howard Pyle. In 2018, it was revealed in an article in The Guardian (London) that Masters was also an all but unknown “early modernist” photographer, who used photography to make reference images for his illustrations. Most of his photographs were cyanotypes, one of which is shown above.

Only a few days ago, I was fortunate to run across an online statement, written by Masters in 1920, in a book of first person updates by members of the MIT graduates of 1895. Reprinted below, it provides a postwar account of his service as a camoufleur.

•••

Frank Bird Masters, “Camouflage and Camoufleur” in Class of 1895 Book: 25th Anniversary, MIT. Boston, 1920, pp. 162-163—

Much has been written about “camouflage,” but nothing authentic has been published about marine camouflage except one magazine article: “The Inside Story of Marine Camouflage” by Everett L. Warner USNRF in Everybody’s Magazine, November 1919. Because of the popular misconception of this subject, [the following] notes may be of interest:

Although all sorts of ingenious attempts were made to really “camouflage” ships, all were futile from the point of view of the submarine, for no paint could make a moving ship look like its background—the sky. So, instead of protective coloration, the basis of all camouflage, “dazzle painting,” was developed during 1918, not to make a ship unseeable, but to make it unhittable by deceiving the submarine commander as to the actual course of the ship. Reverse perspective, not only of lines and masses, but of color and other optical devices made the ship appear, through the “sub” periscope, to be on a course several points off its true course, thus making the sub commander’s calculations wrong and the torpedo attack ineffective. But a very small fraction of one per cent of the “dazzle painted” American ships were torpedoed.

After the establishment of a Camouflage Section, early in 1918, the Navy Department took over all production of “designs,” and the work of applying the dazzle painting to all ships was put under the sole supervision of the US Shipping Board Camoufleurs. The Camoufleur was Uncle Sam’s boss on the job. With the aid of two painters the ships were “marked out,” the “design” being carefully adapted to the ship’s variation from “type,” then the painting was carried on under the direction and supervision of the Camoufleur, who kept in constant touch with the District Camoufleur’s office, turning in daily reports of all camouflage activities.

[I, Frank B. Masters] Camouflaged Morey’s first ship, the Bedminster, at Sachronville in August 1918.*

After a period of intensive training in the “inside dope” of designing at the Camouflage Section of the Navy Department at Washington DC, in September 1918, I was fortunate in being able to devote considerable time to experimental work and original design—helping to develop a “camouflage testing theatre,” through the periscope of which camouflage scale models were tested under all conditions of light, atmosphere, etc. Developed a method by which a sketch could be quickly made showing the appearance of camouflage ships from a point of view 3 or 4 points off the bow—a sure test of the effectiveness of a new design. Made many photographs of models and all sorts of drawings for the US Shipping Board Report on Camouflage which I understand has been turned over to Prof [Cecil Hobart] Peabody and MIT.

* As of this writing, I have not been able to find what the term “Morey’s” refers to, nor further information about a ship named Bedminster, or a location called Sachronville. I have found that the same camouflage pattern used on Bedminster was also applied to the SS Alvado, SS Lake Osweya, and SS Lake Pepin.

Monday, October 17, 2022

a motley-looking crowd of the weirdest description

|

| USS Wakulla (1918) in dazzle camouflage |

We were in the harbor of a famous Southern port [in England] on board the leader of a destroyer flotilla ready to start on one of its ordinary cruises as escort to merchant convoys. It was a cold, bleak stormy day, with a cross sea running in the Channel. One after the other the members of the flotilla cast off from the buoys, and slipped silently seaward. In the outer harbor were the huge merchantmen we were to escort into the comparative safety of the broad Atlantic. They were a strange motley-looking crowd, with a camouflage appearance of the weirdest description, calculated to send Futurist artists into ecstasies. These weird-looking vessels followed the destroyers in single file out of harbor at slow speed until well out into the Channel. There they were formed up and made into as compact a crowd as possible. A destroyer in front and others on each flank constituted a protective screen. After we had got well out and had lined up our escort full speed ahead was ordered, but that was full speed for the convoy only. The destroyers were at about halfspeed, and this was partly expended in zigzagging. To and fro, without a moment’s respite, the leader proceeded in front of the convoy, always about 500 to 600 yards ahead, as though showing to timid followers that it was perfectly safe to follow where we led. On the flanks other destroyers kept up the same zigzag procedure, and astern yet another zigged and zagged and did her best to keep the rearmost ships up to the full convoy speed.

Sunday, October 16, 2022

Caligari, distorted film sets and WWI ship camouflage

•••

Herman George Scheffauer, “The Vivifying of Space” in The New Vision in German Arts. London: Ernest Benn, 1924—

[his description of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari] Trees are resolved into conventionalized, constructed forms; foliage becomes a mass of light, dark and shaded crescents, rounds and silhouettes—brilliantly colored in the original scene. Floors and pavements are streaked, splashed and spotted, divided and decorated in bars, crosses, diagonals, serpentines and arrows. The walls become as banners or as transparencies, space fissued by age, or as slates upon which the lightning blazes strange hieroglyphs; or they become veils and vanish in a mosaic of scrambled forms and surfaces, like a liner in camouflage.

Gaunt chimneys rear and slant like masts in this city storm. Cunning lines of composition and the adroit use of diagonals drive the perspective into an invisible “vanishing point.”

For more on the Caligari film sets, forced perspective, and other early avant-garde cinema, see Part Three of my recently posted video trilogy on the Ames Demonstrations here.