|

| Ship Camouflage Scheme (starboard) / Frederick A. Pawla |

The facts of his life are at issue as well. It seems that he was born in Wimbledon, England, in 1876 (another source claims Scotland), but left home at age 14 to become a sailor. Various sources make differing claims: Some say that he left home to join the US Navy, but a news article from 1952 states that he left London not for the US but for Sydney AU, where he worked on Australian government ships. He eventually turned to painting and studied there with Australian marine painter William Lister Lister. But “the wanderlust seized him and he came to the United States.” Others claim that he was a scout in the Boer War, that he participated in the first Chino-Japanese war (1894-95), and that he served in the US Merchant Marine.

In that 1952 news article, when he and his wife had recently moved to Santa Cruz CA, Pawla was said to have previously lived on the French Riviera, in Hawaii, Tahiti, and Australia, as well as in various regions of the US.

According to ship modeler Aryeh Wetherhorn, Pawla was a “highly important” marine camoufleur for the US during World War I, but is now “largely forgotten.” On Wetherhorn’s website are screen shots of government documents from the NARA (National Archives and Records Administration), in which Pawla is listed as having originated the “dazzle” camouflage designs for various ships, but is insufficiently credited because he is listed as Paula.

His wartime contributions to camouflage service are noted only briefly in another news article from 1922, when he and his wife had resettled from New York to Tampa FL. It is also stated that he had made a painting of the USS Leviathan, which “earned for the artist an official commendation of the highest kind.”

Following WWI, Benedict Crowell, US Assistant Secretary of War, openly applauded Pawla’s camouflage efforts. In 1921, Crowell wrote an overview of the war. He noted that dazzle-painting was officially adopted in 1917 as standard practice for American ship camouflage, made possible by a consensus among the US Navy, the Shipping Board, and the Embarkation Service of the AEF (American Expeditionary Forces, which at the time was the title for the US Army).

Pawla was in charge of camouflage for the AEF Embarkation Service. He oversaw the camouflage of “many of the army transports, particularly cargo carriers,” and, according to Crowell, was “one of the most valuable men in the Government for this sort of work.” But most accounts of WWI American ship camouflage are focused on the efforts of the Navy and the Shipping Board, and the fact that Pawla was associated with the Army may also explain why his work is infrequently cited. At least two post-war news articles state that he worked for the Army, one of which claims that he “was commissioned as an officer in the infantry, after which he took charge of the inauguration of camouflage in the army transport service.”

If he oversaw the camouflage of cargo ships that transported horses, equipment and other supplies to Europe, it may not necessarily mean that he himself designed the actual camouflage schemes. As Wetherhorn goes on to note—

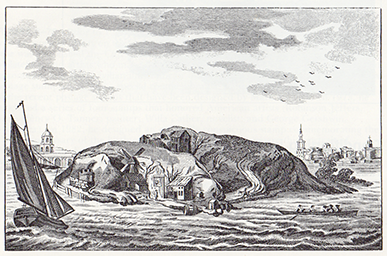

At the same time, his direct involvement in designing camouflage may be confirmed in other ways. In recent years, concurrent with the WWI Centenary, a limited number of full-color diagrams for WWI ship camouflage schemes (hand-colored in gouache in some cases, or more often as lithographic prints) have been scanned and posted on US government websites. The artists who designed the schemes are sometimes noted in red pencil, and the name Pawla is clearly written on several of those. One of those prints is reproduced at the top of this page.

A duplicate, nearly complete set of the lithographic prints (455 in number) is in the collection of the Fleet Library at the Rhode Island School of Design, but they lack the penciled-in names of the artists who designed them.

While the sources are unlisted, Wetherhorn* provides a list of ships that he credits as having been “camouflaged” by Pawla. With considerable effort, one can find photographs of the majority of these ships, but not when they were covered with dazzle patterns. His list includes the following (when I’ve wondered if ship names were incorrectly listed, I’ve added suggested alternatives in brackets): SS Arcadia, SS Bayano [SS Bayamo?], SS Buford, SS City of Atlanta, SS Duca Degli Abruzzi, SS Hewitt, SS Kilpatrick, SS Montanian [SS Montanan?], SS Munwood, SS Pennsylvanian [USS Scranton], SS Eagle, SS El Occidente, SS El Sol, SS Findland [SS Finland?], SS Floridian, SS George H. Henry, SS Itaska, SS Kentuckian, SS Edward Luckenbach, SS Medina, SS Montosa [SS Montoso?], SS Newton, SS Neches, SS Oregonian, Rondo [SS War Wonder?], SS Panaman, SS San Jacinto, SS Tamayo, SS Tiger, SS Tivies [SS Tivives?], SS Tungus [SS Tongos?] and SS Tyr.

|

| USS Panaman (c1918) in dazzle camouflage |

I was able to find a photograph of the dazzle-painted USS Panaman (reproduced above), and there are also online images of several ships that were named after various members of the Luckenbach family, the USS Edward Luckenbach being one. During WWI, the Luckenbach Steamship Company, headed by Edgar F. Luckenbach, supplied at least eight cargo ships for the purpose of transporting troops. In a document dated 1918, Edwin F. Luckenbach is on a list of those who studied ship camouflage in New York under William Andrew Mackay.

Based on material online, especially historic newspapers, Pawla may have accomplished considerably more as a ship camoufleur than he did as an artist in subsequent years. As a civilian artist, according to the 1952 news article, “His greatest work, in point of both magnitude and interest, is a cyclorama of [the Battle of] Chateau-Thierry, which has been exhibited in many of the large cities in the US.” This may be the same cyclorama that was installed at Luna Park in Coney Island in 1927. News reports in Brooklyn described it as follows—

fifty feet high and three hundred [and] sixty-five feet in circumference. There are more than one thousand sheets of galvanized iron, eight feet long, weighing seven and one-half tons. There are two thousand electric lamps with fifteen thousand additional watts to produce the varied effects.…As you stand on an elevated platform, you see the war fields, machine gun nests, snipers, heavy artillery and airplanes in action, in one of the world’s most exacting struggles.

An earlier cyclorama had recreated the Battle of Gettysburg, but this one for Chateau-Thierry, a journalist claimed, was “the most sensational and educational attraction ever brought to this famous resort” and “has broken all records for attendance.” Regrettably, neither Pawla nor any other artists are mentioned as being responsible for the cyclorama.** ***

Pawla’s other artwork is not so illustrious. In California, he is credited with having created three murals (the main panel is seventy feet wide) about California history for installation at the high school in Burlingame CA. For years, these were said to have been commissioned by the government as Depression-era WPA (Works Progress Administration) public artworks. But several contemporaneous news articles make it clear that the murals were completed in 1934 and purchased by the school itself, using funds raised by the students.

•••

* Another interesting post by Wetherhorn (not on his website but on the Naval History Blog) is a brief account of the camouflage contributions of the well-known American artist Arthur B. Carles and his sister Sara Elizabeth Carles. His post provides considerable insight into the activities of Sara Carles and other American women in connection with ship camouflage. Reproduced on the page are several Reports on Camouflaged Ships, indicating that these women were land observers (not designers of camouflage schemes) who were stationed at various harbors and assigned to making colored drawings/paintings of any camouflaged ships that they observed, both US and others. As we have blogged about earlier, Thomas Hart Benton had the same assignment at Norfolk, as did other artists.

** Update (same day as original post): Having now searched further in online newspapers, I am increasingly hesitant about crediting Pawla with the Chateau-Thierry cyclorama. I have found no mention of his name. Instead, I have now discovered reports that say it was an "imported cyclorama" and that the actual painting required the skills of "eighteen French painters." At the same time, how many Chateau-Thierry cycloramas can there be? Perhaps he supervised the project and/or its installation at Coney Island.

*** In an essay published a few years ago, titled "Setting the Stage for Deception: Perspective Distortion in World War I Camouflage" (full text online), we talked about the relatedness of the use of forced perspective in cycloramas and ship camouflage.

Sources

Anon. Recollections of… Brooklyn Life and Activities of Long Island Society (Brooklyn NY), May 14, 1927, p. 19.

Anon. The cyclorama… Brooklyn Life and Activities of Long Island Society (Brooklyn NY) , August 13, 1927, p. 16.

Anon. MURAL ARTIST IN TAMPA TO OPEN STUDIO: WAS IN CAMOUFLAGE DEPARTMENT. The Tampa Tribune (Tampa FL) November 3, 1922, p. 7.

Anon. PAWLA PAINTINGS ON EXHIBIT SOON AT BURLINGAME HI. San Mateo Times (San Mateo CA), April 20, 1934.

Crowell, Benedict. The Giant Hand: Our Mobilization and Control of Industry and Natural Resources, 1917-1918. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1921.

Hanifin, Ada. Paintings by Pawla on View: Soldier-of-Fortune and Veteran of Many Wars Holds One-Man-Show of Ships at Gumps, in San Francisco Examiner, Sunday, February 4, 1934.

Rawson, Laura. FAMED MARINE ARTIST FREDERICK PAWLA NOW LIVING IN SANTA CRUZ in Santa Cruz Sentinel-News, November 7, 1952, p. 2.