|

| Alfred Stieglitz, Hands of Helen Freeman (c1920) |

Everyland, an American monthly periodical published by Christian missionaries, was self-described as "a magazine of world friendship for boys and girls." Among its various activities, it sponsored drawing contests. In its June 1920 issue (Vol 11 No 6), it included the following paragraph—

Morgan Stinemetz…is our Art Editor. During the war, he was in the camouflage service of the navy. It is he who will judge the results of the drawing contests, so look out for him!

So who was Morgan Stinemetz? In addition to that page in

Everyland, I've found two other sources. One is a multi-page article by Louise Davis, titled

ARTIST'S RETREAT: Morgan Stinemetz, who dropped an illustrator's career to become Methodist Publishing House art editor, is a man who finds joy in country life. Published in

The Nashville Tennessean Magazine on September 7, 1952 (pp. 6-7, 18-19), it was illustrated by eight photographs of the artist and his artwork, interwoven with interview excerpts. I also found a newspaper obituary that was featured in the

Nashville Tennessean on August 20, 1969 (p. 23). He had died at a nursing home in Nashville two days earlier.

Stinemetz was born in Washington DC in 1886. His grandfather,

Major Thomas P. Morgan, was one of the first DC police commissioners. His father-in-law was an important DC publisher. As a child, Stinemetz had been interested in animals, as well as in painting and drawing. He studied at the Corcoran School of Art in DC, the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia with

Thomas P. Anshutz, a student and later a colleague of Thomas Eakins.

From Philadelphia, Stinemetz returned to New York, where (these are Louise Davis' words)

"cubism and other various other 'isms' that startled the new century were taking a firm hold. He experimented with all of them and had his paintings in numerous shows, including the first International Art Show at the Armory in New York in 1913, when Matisse and Picasso were first shown in this country."

He became interested in the literary excursions of

Gertrude Stein, and developed a friendship with

Alfred Stieglitz, photographer, gallery owner, and the publisher of

Camera Work. In 1916, Stieglitz met the painter

Georgia O'Keeffe, and soon after they became a pair. It is interesting to note that in the years just prior to this, O'Keeffe had studied with an art educator (and an advocate of the theories of

Arthur Wesley Dow) named

Alon Bement, who had been her greatest influence. During World War I, Bement was a major contributor to American

ship camouflage.

As for Stinemetz, he soon became disillusioned with Modernism. Quoting Davis, he became

"fed up with the artificiality of the whole movement." At gallery openings, when he mingled with those in attendance,

"he overheard them 'interpreting' things into his work that he had never thought of. …They analyzed every brush stroke, he said, and he was sick of it. He gave up painting on the spot," and turned instead to a new career as a book and magazine illustrator. In subsequent years, he became a well-known illustrator for a variety of popular magazines, among them

Collier's,

Cosmopolitan,

Good Housekeeping,

Outdoor Life, and others. He especially enjoyed animal illustrations, and eventually became well-known for his drawings and prints of Scottie dogs. Over the years, he moved from the East Coast to Cincinnati, then settled in Nashville TN as the art director for the Methodist Publishing House.

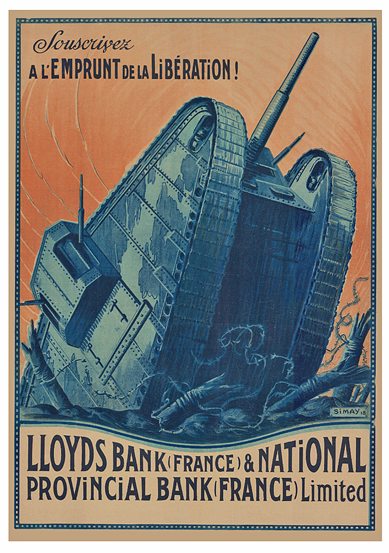

The US entered WWI in 1917, and soon after artists, designers and architects were encouraged to use their expertise in the development of wartime camouflage. Stinemetz was one of those who contributed to naval camouflage. The article by Davis states that

"he served in the navy, capitalizing on the tricks of cubism to camouflage our ships so that enemy submarines would miscalculate their aim." The obituary simply notes that

"he designed camouflage for ships of the US Navy." But he may have remained a civilian, since the Navy and the US Shipping Board worked with both military and civilian artists in designing, testing and painting "dazzle" camouflage patterns on ships, both military and commercial (called merchant ships).

Until these references were found, I had never heard of Morgan Stinemetz, much less about his service as a ship camoufleur, so it may be wise to be skeptical of the claim (stated first in the Davis article, then repeated verbatim in the obituary) that "so effective were his

distortions of perspective that a record of his camouflage patterns was filed in various museums." Obviously, if such documents still exist, it would surely be helpful to find them.

Postscript (added May 10, 2019): I was mistaken. I

had heard of Morgan Stinemetz. A couple of years ago, I gained access to a list (dated September 26, 1918) of sixty-four artists who had studied ship camouflage in New York with

William Andrew Mackay. Stinemetz's name is on that list of American Shipping Board camoufleurs from the Second District. This suggests that Stinemetz was a civilian, and most likely not in the Navy.