In July 2020,

we posted on this blog an account of the launching (on July 29, 1918 at Tampa FL) of an American merchant ship, the SS

Everglades. As we explained at the time, it was the first ship in which a camouflage pattern was applied while the ship was still under construction, and in advance of its launching.

In that post, we talked about

Maurice L. Freedman (1898-1983), who was a District Camoufleur for the US Shipping Board, assigned to Jacksonville FL. Freedman is of interest because, following the war, when he enrolled as a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, he donated to its library a nearly complete set of the colored lithographic plans for “dazzle camouflage” schemes that were designed by US Navy camoufleurs in Washington DC. That rare collection has survived and remains in the library's archives at RISD in Providence.

In that same post, we also shared information about another Florida-based ship camoufleur named

Frank Bird Masters (1873-1955), who was present at the launching in Tampa, and who was apparently in charge of applying the camouflage scheme to the SS

Everglades.

More detail is in our original blog post, but it may be sufficient to say that Masters was a magazine and book illustrator who had initially studied science and engineering at MIT, graduating in 1895. A few years later, he changed his profession to that of an illustrator, and studied with well-known artist

Howard Pyle. In 2018, it was revealed in

an article in The Guardian (London) that Masters was also an all but unknown “early modernist” photographer, who used photography to make reference images for his illustrations. Most of his photographs were

cyanotypes, one of which is shown above.

Only a few days ago, I was fortunate to run across an online statement, written by Masters in 1920, in a book of first person updates by members of the MIT graduates of 1895. Reprinted below, it provides a postwar account of his service as a camoufleur.

•••

Frank Bird Masters, “Camouflage and Camoufleur” in

Class of 1895 Book: 25th Anniversary, MIT. Boston, 1920, pp. 162-163—

Much has been written about “camouflage,” but nothing authentic has been published about marine camouflage except one magazine article: “The Inside Story of Marine Camouflage” by Everett L. Warner USNRF in Everybody’s Magazine, November 1919. Because of the popular misconception of this subject, [the following] notes may be of interest:

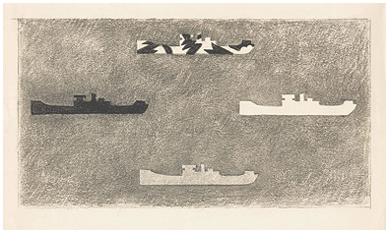

Although all sorts of ingenious attempts were made to really “camouflage” ships, all were futile from the point of view of the submarine, for no paint could make a moving ship look like its background—the sky. So, instead of protective coloration, the basis of all camouflage, “dazzle painting,” was developed during 1918, not to make a ship unseeable, but to make it unhittable by deceiving the submarine commander as to the actual course of the ship. Reverse perspective, not only of lines and masses, but of color and other optical devices made the ship appear, through the “sub” periscope, to be on a course several points off its true course, thus making the sub commander’s calculations wrong and the torpedo attack ineffective. But a very small fraction of one per cent of the “dazzle painted” American ships were torpedoed.

After the establishment of a Camouflage Section, early in 1918, the Navy Department took over all production of “designs,” and the work of applying the dazzle painting to all ships was put under the sole supervision of the US Shipping Board Camoufleurs. The Camoufleur was Uncle Sam’s boss on the job. With the aid of two painters the ships were “marked out,” the “design” being carefully adapted to the ship’s variation from “type,” then the painting was carried on under the direction and supervision of the Camoufleur, who kept in constant touch with the District Camoufleur’s office, turning in daily reports of all camouflage activities.

[I, Frank B. Masters] Camouflaged Morey’s first ship, the Bedminster, at Sachronville in August 1918.*

After a period of intensive training in the “inside dope” of designing at the Camouflage Section of the Navy Department at Washington DC, in September 1918, I was fortunate in being able to devote considerable time to experimental work and original design—helping to develop a “camouflage testing theatre,” through the periscope of which camouflage scale models were tested under all conditions of light, atmosphere, etc. Developed a method by which a sketch could be quickly made showing the appearance of camouflage ships from a point of view 3 or 4 points off the bow—a sure test of the effectiveness of a new design. Made many photographs of models and all sorts of drawings for the US Shipping Board Report on Camouflage which I understand has been turned over to Prof [Cecil Hobart] Peabody and MIT.* As of this writing, I have not been able to find what the term “Morey’s” refers to, nor further information about a ship named Bedminster, or a location called Sachronville. I have found that the same camouflage pattern used on Bedminster was also applied to the SS Alvado, SS Lake Osweya, and SS Lake Pepin.