|

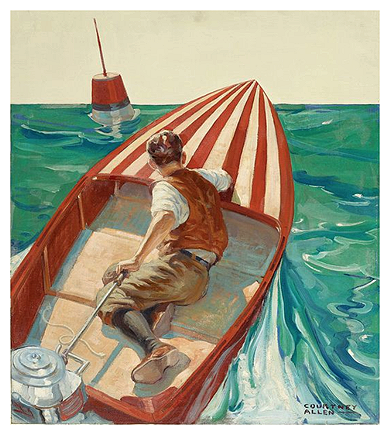

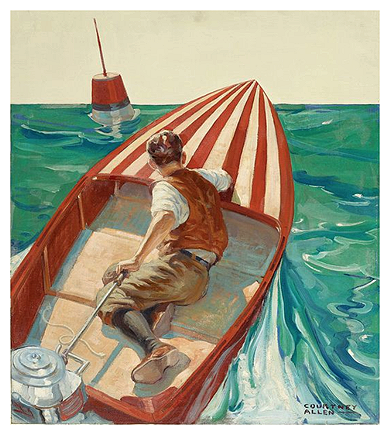

Courtney Allen

|

There was an American illustrator and performer named

Courtney (Charles) Allen (1896-1969), who was also a camouflage artist. He was an interesting character, and he surely deserves recognition. Below is information I found some time ago, which I subsequently shared with askART.

When the US entered World War I in 1917, he was working as an artist for the Wilmington Star and the Washington Times. He joined the US Army and served in France as a camouflage artist. A front page article in the Washington Times in 1919 states that 37 officers and 445 camouflage artists have returned to Washington barracks after ten months of overseas service.

Among the returning camoufleurs, the article states, was Sergeant Courtney C. Allen, “former artist for The Times,” as well as five other artists from Washington DC, including Captain E.R. Keane, Private David Rubin, Private James Allen, Private George Park, and Private James O’Shea. Four of the five were pictured in a group photograph in the same issue, titled “Four Washington ‘Camoufleurs,’ Just Back.” The news photograph (including the headshot of Allen below) has not stood the test of time.

|

Courtney Allen (1919)

|

“Sergeant Allen,” the article continues, “was in the fighting at Chateau-Thierry, Soissons, Saint-Mihiel, and at other points along the American line. ‘At Chateau-Thierry we did our best work,’ he said to a

Times reporter.”

It may also be surprising to learn that Courtney Allen was also a wildly popular stage musician and comic performer. While studying at Charles Hawthorne’s Cape Cod school, he and five other artists (“all veterans of the World War”) established a popular Provincetown MA coffee house, on Lewis Wharf, called the “Sixes and Sevens,” in which they functioned as the cooks, waiters and entertainers. An article and photograph of the “Big Six” players were published in the

Boston Globe in 1920.

In that news feature, Courtney Allen is singled out as especially popular with the crowd. He is, states the article, “variously known among the crowd as ‘Cootie’ Allen and ‘Cuskoo.’” He “is a clever performer with the ukulele and the steel guitar and is kept very busy when the coffee house is crowded—as it has been every evening since it opened.” The raucous new business was seen as a successor to the famous

Provincetown Players, who had moved to McDougal Street in Greenwich Village by then.

In August 1921, Allen is mentioned in a

Boston Post article as having been a great success at the annual Provincetown Costume Ball. Dressed as “a Japanese coolie,” he received an honorable mention in the costume judging. The Second Prize was awarded to artist

Lawrence W. Grant (dressed as a “snake charmer”), who had also served as an Army camouflage artist in France.

For most of his life, he appears to have made his living as a magazine and newspaper illustrator, as in the example shown at the top of this blog post.

Sources

“Camouflage Men Come to Capital” in Washington Times. January 31, 1919, p. 1.

“Costume Ball Like Fairyland” in Boston Post. August 6, 1921.

“Courtney Allen” in Who Was Who in American Art.

Paul Stanwood, “Provincetown Finds Fun at the ‘Sixes and Sevens’ Coffee House” in Boston Globe. July 18, 1920.