|

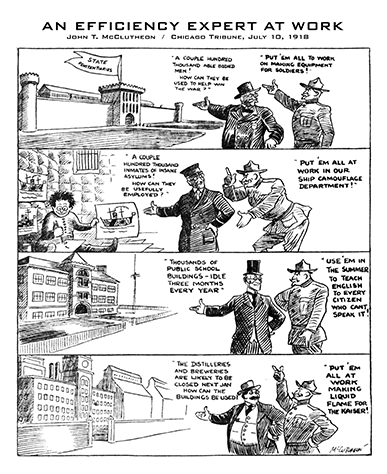

| Detail of John T. McClutcheon cartoon (1918) |

Saturday, August 31, 2019

Eyewitness | WWI dazzle ships not what they seem

Kate Burr, CAMOUFLAGED SHIPS: WHAT THEY SEEM THEY ARE NOT, in Buffalo Times (Buffalo NY) September 4, 1918—

I have seen some of the camouflaged ships which the Government has had painted for war reasons. They were a mile from where I was looking at them, but the glasses were good and brought them near. The three I saw were each one different from the others and gave a different effect to the observer.

For instance, the first of the boats looked like three fastened together and built in some strange elemental fashion with the bow higher than the keel and the middle bulging far over the sides.

It was not any of it so—all the work of the consummate artist in perspective who did the painting.

A little way off the casual onlooker was unable to tell whether the boat was “coming or going.”

The second ship presented the appearance of a battleship bristling and threatening.

The third ship sailed majestically out of the river and so much painted drapery was shown along her sides that I was minded of Tennyson’s Elaine on her flower-decked bier sailing home for her burial place.

The camouflage was complete.

Nobody could tell what was vulnerable, nor what was important, nor where the guns were placed—for though this is a vessel for common carrying, she must be armed we know.

The white body was strangely decorated with blue painting and gray painted, and what was shadow and what was blue water, and what was construction no human eye could determine by its naked strength nor with the help of strong lenses.

It was all wonderful—this camouflage of vessels—this blending of atmosphere and sea and sky.

Turning away in admiration, my eyes sweeping the shore line, discovered an object which lent a little ray of humor in this grim paraphernalia of war.

At one of the private docks belonging to the cottage community was tied a sort of craft which brought us to smiles.

It was a small floating structure about the size and shape of a bathtub, painted in “battleship gray.”

At first sight that was all—but—and then the smiles grew deep—along the sides were wide markings of blue and gray—stripes and festoons and circles and oblongs.

Some imitative lad of seven or ten had persuaded his Daddy to furnish the paint and ingenuity had accomplished the rest.

No warring enemy submarine will seek out this protected craft, which is surely a merchantman—carrying supplies from the mainland to a fairy island where busy and saddened people congregate to forget war for a few brief days before getting into the thick of work for their boys and their government again.…

Thursday, August 29, 2019

Wednesday, August 28, 2019

Women camoufleurs Louise Larned and Rose Stokes

Above Government photograph of an unidentified US Navy Yeoman (F) (or Yeomanette), c1918. Assigned to the Camouflage Section in Washington DC, she is assembling wooden ship models, which were later painted with camouflage schemes, and tested for effectiveness.

•••

Louise Larned (1890-1972), whose married name was Louise Larned Fasick (she married John E. Fasick in 1929), is sometimes confused with her mother, Louise Alexander Larned (1862-1949). Her father was US Army Colonel Charles William Larned (1850-1911), who briefly served with General George A. Custer in the Seventh Cavalry, but is more commonly known for having taught drawing at West Point Military Academy for 35 years.

Both parents were descended from a long line of military officers, and Louise grew up in the vicinity of West Point. She followed her father’s aptitude for drawing, as well as her family's tradition of serving in the military.

At the beginning of World War I, American women were not allowed to officially serve in the military, but they could provide supporting roles as civilians. In an article in the New York Tribune, Anne Furman Goldsmith, the New York chairman of “a proposed camouflage unit of women for service in the United States,” called for women to enroll in the organization. It was planned that they would be trained at a four- to six-week camp by a camouflage expert, and then sail off to duty in France. “There is no age limit for the volunteers,” the article stated, but “they must be physically strong and active, however, and have some knowledge of landscape, mural or scene painting.”

The acceptance of Goldsmith’s proposal was repeatedly delayed (according to the War Department, “it could not spare an instructor”) until the unit was finally established in 1918, with the official title of the Camouflage Corps of the National League for Women’s Service in New York. Louise Larned volunteered in May of 1918 and joined a group that was taught by artist H. Ledyard Towle. Joining at the same time was another woman artist, with strong connections to West Point, Rose Stokes.

After attending the camouflage camp, the women camoufleurs (who were sardonically nicknamed “camoufleuses” or “camoufloosies”) took on other projects, most of which used “dazzle” camouflage to attract larger crowds to recruiting and fund-raising events. Overnight, on July 11, 1918, for example, twenty-four of the women camouflage artists painted a multi-colored disruption scheme (using abstract, geometric shapes in black, white, pink, green, and blue) on the USS Recruit, a wooden recruiting station in Union Square in NYC, built to convincingly look like a ship. Louise Larned and Rose Stokes were members of that painting team.

In September 1918, both Larned and Stokes were assigned to the Navy’s Camouflage Section, where they probably made model ships (to which camouflage was applied for testing) or, as draftsmen, prepared large scale colored diagrams for use by artists at the docks in painting camouflage on the ships.

They had expected to remain on duty until the war’s official end. But the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919, and exactly one month later, newspapers announced that most of the eleven thousand women “yeomanettes” would be discharged early. But certain women were retained, with Larned and Stokes among them. More details were provided by the Pittsburgh Post:

“Among those who will remain are the artist girls who drew dazzle designs for merchant and battleships—those funny zig-zag stripes which made the Germans waste torpedoes and valuable shells on ships which appeared to be ‘going the wrong way.’ The artists today were working on submarine plans and they like the life.

“‘I do wish the newspapers would say we don’t want to leave the navy,’ said Louise Larned, one of the artistic yeomanettes. ‘We want to be part of the service.’

“And Rose Stokes, whose brothers are all West Pointers, wants to ‘be in the navy—not just a barnacle attached to it by civil service rules.’”

Two months later, a woman journalist named Edith Moriarty published an article in the Spokane Chronicle in which she said that, during the war, the government had discovered that women are just as good or better than men at drawing-related tasks, such as drafting charts and diagrams.

She continued: “Two young women who made good along that line are Miss Rose Stokes of New York and Miss Louise Larned, of West Point NY. These girls, who are both artists, enlisted in the navy as yeomen and they were in New York in the camouflage corps studying to go abroad when the armistice was signed. They have spent most of their time while in the service putting in details on specifications and charts for submarines. The girls are so satisfactory at their work that they have been retained by the navy although many of the yeomen have been relieved of further duty.”

It has so far proved a challenge to locate more specific facts about the life of Louise Larned Fasick. One additional finding is that she was the designer of what was known as the “Navy Girl Poster,” which was presumably used to recruit women to serve in the navy.

•••

Update (August 29, 2019) Sorry, haven't yet located an image file for Louise Larned's poster (there are well-known posters by that tag but they appear to have been the work of Howard Chandler Christy). However, we have located three paintings by Louise Larned and one by Rose Stokes. Of the four, three are government paintings of ships (two by Larned, one by Stokes), in public domain, and the fourth is a pastel cover painting for St. Nicholas Magazine (by Larned), dated 1929. They are reproduced below.

Above Louise Larned, Ocean-Going Tug Towing Target Shed (n.d.)

Above Louise Larned, Ship of the Nevada Class (n.d.)

Above Rose Stokes, South Dakota Class Battleship, Concept Drawing (n.d.) [at a cursory glance from a distance, it looks almost identical to the previous Larned painting]

Above Louise Larned, Cover painting for the September 1929 issue of St. Nicholas Magazine.

•••

Sources

Women Artists Asked For Camouflage Unit: Miss Anne F. Goldsmith Wants One Hundred To Train for Service in France. New York Tribune, October 24, 1917.

Camouflage the Recruit: Woman’s Service Corps Redecorate the Landship in Union Square. Washington Post, May 14, 1918.

Yeomen Rejoice; End of Jobs’ Scorn Is Sighted as Yeomanettes Leave Navy; Girls Establish Good Record. Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh PA), July 28, 1919.

Edith Moriarty, With the Women of Today. Spokane Chronicle (Spokane WA), September 18, 1919.

Roy R. Behrens, ed., Ship Shape: A Dazzle Camouflage Sourcebook. Dysart IA: Bobolink Books, 2012.

•••

Earlier, I had posted a newspaper photograph of Louise Larned and Rose Stokes (NY Tribune, August 7, 1919) at work drafting plans for submarines. But the picture quality was so poor that I decided to remove it. Nevertheless, the caption for the photograph may still be of interest. It reads: These girls drew submarine plans for the US Navy instead of knitting socks during the war. They enlisted in the navy as yeomen and were in the camouflage corps in New York studying to go abroad when the armistice was signed. Both girls are artists and will be retained by the navy after yeomanettes are relieved. Miss Rose Stokes of New York City is commander of the Betsy Ross Chapter of the American Legion…

Note A somewhat different version of this post has also been provided to AskART.com.

•••

Louise Larned (1890-1972), whose married name was Louise Larned Fasick (she married John E. Fasick in 1929), is sometimes confused with her mother, Louise Alexander Larned (1862-1949). Her father was US Army Colonel Charles William Larned (1850-1911), who briefly served with General George A. Custer in the Seventh Cavalry, but is more commonly known for having taught drawing at West Point Military Academy for 35 years.

Both parents were descended from a long line of military officers, and Louise grew up in the vicinity of West Point. She followed her father’s aptitude for drawing, as well as her family's tradition of serving in the military.

At the beginning of World War I, American women were not allowed to officially serve in the military, but they could provide supporting roles as civilians. In an article in the New York Tribune, Anne Furman Goldsmith, the New York chairman of “a proposed camouflage unit of women for service in the United States,” called for women to enroll in the organization. It was planned that they would be trained at a four- to six-week camp by a camouflage expert, and then sail off to duty in France. “There is no age limit for the volunteers,” the article stated, but “they must be physically strong and active, however, and have some knowledge of landscape, mural or scene painting.”

The acceptance of Goldsmith’s proposal was repeatedly delayed (according to the War Department, “it could not spare an instructor”) until the unit was finally established in 1918, with the official title of the Camouflage Corps of the National League for Women’s Service in New York. Louise Larned volunteered in May of 1918 and joined a group that was taught by artist H. Ledyard Towle. Joining at the same time was another woman artist, with strong connections to West Point, Rose Stokes.

After attending the camouflage camp, the women camoufleurs (who were sardonically nicknamed “camoufleuses” or “camoufloosies”) took on other projects, most of which used “dazzle” camouflage to attract larger crowds to recruiting and fund-raising events. Overnight, on July 11, 1918, for example, twenty-four of the women camouflage artists painted a multi-colored disruption scheme (using abstract, geometric shapes in black, white, pink, green, and blue) on the USS Recruit, a wooden recruiting station in Union Square in NYC, built to convincingly look like a ship. Louise Larned and Rose Stokes were members of that painting team.

In September 1918, both Larned and Stokes were assigned to the Navy’s Camouflage Section, where they probably made model ships (to which camouflage was applied for testing) or, as draftsmen, prepared large scale colored diagrams for use by artists at the docks in painting camouflage on the ships.

They had expected to remain on duty until the war’s official end. But the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919, and exactly one month later, newspapers announced that most of the eleven thousand women “yeomanettes” would be discharged early. But certain women were retained, with Larned and Stokes among them. More details were provided by the Pittsburgh Post:

“Among those who will remain are the artist girls who drew dazzle designs for merchant and battleships—those funny zig-zag stripes which made the Germans waste torpedoes and valuable shells on ships which appeared to be ‘going the wrong way.’ The artists today were working on submarine plans and they like the life.

“‘I do wish the newspapers would say we don’t want to leave the navy,’ said Louise Larned, one of the artistic yeomanettes. ‘We want to be part of the service.’

“And Rose Stokes, whose brothers are all West Pointers, wants to ‘be in the navy—not just a barnacle attached to it by civil service rules.’”

Two months later, a woman journalist named Edith Moriarty published an article in the Spokane Chronicle in which she said that, during the war, the government had discovered that women are just as good or better than men at drawing-related tasks, such as drafting charts and diagrams.

She continued: “Two young women who made good along that line are Miss Rose Stokes of New York and Miss Louise Larned, of West Point NY. These girls, who are both artists, enlisted in the navy as yeomen and they were in New York in the camouflage corps studying to go abroad when the armistice was signed. They have spent most of their time while in the service putting in details on specifications and charts for submarines. The girls are so satisfactory at their work that they have been retained by the navy although many of the yeomen have been relieved of further duty.”

It has so far proved a challenge to locate more specific facts about the life of Louise Larned Fasick. One additional finding is that she was the designer of what was known as the “Navy Girl Poster,” which was presumably used to recruit women to serve in the navy.

•••

Update (August 29, 2019) Sorry, haven't yet located an image file for Louise Larned's poster (there are well-known posters by that tag but they appear to have been the work of Howard Chandler Christy). However, we have located three paintings by Louise Larned and one by Rose Stokes. Of the four, three are government paintings of ships (two by Larned, one by Stokes), in public domain, and the fourth is a pastel cover painting for St. Nicholas Magazine (by Larned), dated 1929. They are reproduced below.

Above Louise Larned, Ocean-Going Tug Towing Target Shed (n.d.)

Above Louise Larned, Ship of the Nevada Class (n.d.)

Above Rose Stokes, South Dakota Class Battleship, Concept Drawing (n.d.) [at a cursory glance from a distance, it looks almost identical to the previous Larned painting]

Above Louise Larned, Cover painting for the September 1929 issue of St. Nicholas Magazine.

•••

Sources

Women Artists Asked For Camouflage Unit: Miss Anne F. Goldsmith Wants One Hundred To Train for Service in France. New York Tribune, October 24, 1917.

Camouflage the Recruit: Woman’s Service Corps Redecorate the Landship in Union Square. Washington Post, May 14, 1918.

Yeomen Rejoice; End of Jobs’ Scorn Is Sighted as Yeomanettes Leave Navy; Girls Establish Good Record. Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh PA), July 28, 1919.

Edith Moriarty, With the Women of Today. Spokane Chronicle (Spokane WA), September 18, 1919.

Roy R. Behrens, ed., Ship Shape: A Dazzle Camouflage Sourcebook. Dysart IA: Bobolink Books, 2012.

•••

Earlier, I had posted a newspaper photograph of Louise Larned and Rose Stokes (NY Tribune, August 7, 1919) at work drafting plans for submarines. But the picture quality was so poor that I decided to remove it. Nevertheless, the caption for the photograph may still be of interest. It reads: These girls drew submarine plans for the US Navy instead of knitting socks during the war. They enlisted in the navy as yeomen and were in the camouflage corps in New York studying to go abroad when the armistice was signed. Both girls are artists and will be retained by the navy after yeomanettes are relieved. Miss Rose Stokes of New York City is commander of the Betsy Ross Chapter of the American Legion…

Note A somewhat different version of this post has also been provided to AskART.com.

Tuesday, August 27, 2019

Cubicular camouflage | the blossoming of crazy quilts

Above Still image from a Pathé film titled Rigadin Cubist Painter (1912).

•••

Caught the Cubist Fashion in Baltimore Sun (Baltimore MD), June 22, 1918—

The camoufleur is having engagements at this port changing the appearance of the local fleet of steamers that enter the war zone declared by the U-boats on this coast. One arrived yesterday from the south so completely disguised by the cubist artist as not to be recognized by agents of her line. Others belonging here are being camouflaged.

•••

Anon in Sioux City Journal (Sioux City IA), August 29, 1921—

Little is seen or heard nowadays about the writers of vers libre ["free verse"] or the cubist artists. Maybe they have gone where they belong—to Camouflage.

•••

PARIS PUTS ARTISTS IN ARMY TO CAMOUFLAGE TRUCKS, TANKS, CANNON: Cubists, Surrealists and Futurists Put Fantastic Designs and Theories Into Practice in the Scranton Times-Tribune (Scranton PA), September 22, 1939—

Cubist, surrealist, modernist, futurist, realist, and naturalist painters who once cluttered Montparnasse terraces are in the army as camouflage artists.

Canvases and theories have been put aside. Long-haired, bearded, shabbily-dressed dreamers have left attics to become clean-shaven, neatly-dressed army men.

Trucks, tanks, armored cars, motorcycles, cannon and staff cars are blossoming with fantastic crazy-quilt designs done in reds, blues, greens, and ochres. Many-schooled cafe arguments have turned into a joint pooling of ideas to befuddle the enemy.

•••

Says "Abstractionist" Painter Should Make Camouflage Experts, in Mason City Globe Gazette (Mason City IA) January 8, 1942—

[Laszlo Moholy Nagy, founder and director of the New Bauhaus school in Chicago], addressing a Drake University audience [yesterday in Des Moines], explained:

"The cubist painters' angular pictures often are the most confusing thing in art to the layman and they are the most talented to turn out camouflage which will confuse the enemy."

"White outs," a system of confusing enemy planes by careful illumination and reflections, would be much more effective than black outs, he declared.

•••

Caught the Cubist Fashion in Baltimore Sun (Baltimore MD), June 22, 1918—

The camoufleur is having engagements at this port changing the appearance of the local fleet of steamers that enter the war zone declared by the U-boats on this coast. One arrived yesterday from the south so completely disguised by the cubist artist as not to be recognized by agents of her line. Others belonging here are being camouflaged.

•••

Anon in Sioux City Journal (Sioux City IA), August 29, 1921—

Little is seen or heard nowadays about the writers of vers libre ["free verse"] or the cubist artists. Maybe they have gone where they belong—to Camouflage.

•••

PARIS PUTS ARTISTS IN ARMY TO CAMOUFLAGE TRUCKS, TANKS, CANNON: Cubists, Surrealists and Futurists Put Fantastic Designs and Theories Into Practice in the Scranton Times-Tribune (Scranton PA), September 22, 1939—

Cubist, surrealist, modernist, futurist, realist, and naturalist painters who once cluttered Montparnasse terraces are in the army as camouflage artists.

Canvases and theories have been put aside. Long-haired, bearded, shabbily-dressed dreamers have left attics to become clean-shaven, neatly-dressed army men.

Trucks, tanks, armored cars, motorcycles, cannon and staff cars are blossoming with fantastic crazy-quilt designs done in reds, blues, greens, and ochres. Many-schooled cafe arguments have turned into a joint pooling of ideas to befuddle the enemy.

•••

Says "Abstractionist" Painter Should Make Camouflage Experts, in Mason City Globe Gazette (Mason City IA) January 8, 1942—

[Laszlo Moholy Nagy, founder and director of the New Bauhaus school in Chicago], addressing a Drake University audience [yesterday in Des Moines], explained:

"The cubist painters' angular pictures often are the most confusing thing in art to the layman and they are the most talented to turn out camouflage which will confuse the enemy."

"White outs," a system of confusing enemy planes by careful illumination and reflections, would be much more effective than black outs, he declared.

Labels:

artists,

avant garde,

Bauhaus,

camo,

camopedia,

camouflage,

Cubism,

dazzle,

French camoufleurs,

humor,

WWI,

WWII

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

A camouflaged cure for a morning hangover

Below This camouflage cartoon by American artist Walter Hoban (1890-1939) was featured in his comic strip Jerry on the Job. It was published in the Oregon Daily Journal (Portland OR) on August 16, 1917.

A CAMOUFLAGE DRINK in the Times-Tribune (Scranton PA) on December 11, 1917—

Making the morning after seem like the night before is the mission of the camouflage, the newest drink. Camouflage, as every student of the war knows, means "making things seem what they ain't." Thus the camouflage looks like a glass of milk, but has the far different effect so much desired on cold, gray mornings. In a word it is a "pick me up" that no man need blush to order after he gets into his working clothes. It is composed as follows: One-half jigger of apple brandy, a half jigger of dry gin, white of an egg, tablespoon of cream and a pinch of powdered sugar. The mixing glass should then be filled with cracked ice, the contents shaken well and strained into a small tumbler. Take two of these and, it is said, one hears sweet music; three and one grabs the next ship for the land of hot dogs, limburger and sauerkraut to take a wallop at the kaiser.

•••

CAMOUFLAGE in the Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer (Bridgeport CT) on October 13, 1917—

If I could use war tactics,

Said the football player fellow,

I'd camouflage the pigskin

By painting it bright yellow;

We'd then fool our opponents,

And win the game hands high,

'Cause they'd think we had a pumpkin

And were going to make a pie.

A CAMOUFLAGE DRINK in the Times-Tribune (Scranton PA) on December 11, 1917—

Making the morning after seem like the night before is the mission of the camouflage, the newest drink. Camouflage, as every student of the war knows, means "making things seem what they ain't." Thus the camouflage looks like a glass of milk, but has the far different effect so much desired on cold, gray mornings. In a word it is a "pick me up" that no man need blush to order after he gets into his working clothes. It is composed as follows: One-half jigger of apple brandy, a half jigger of dry gin, white of an egg, tablespoon of cream and a pinch of powdered sugar. The mixing glass should then be filled with cracked ice, the contents shaken well and strained into a small tumbler. Take two of these and, it is said, one hears sweet music; three and one grabs the next ship for the land of hot dogs, limburger and sauerkraut to take a wallop at the kaiser.

•••

CAMOUFLAGE in the Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer (Bridgeport CT) on October 13, 1917—

If I could use war tactics,

Said the football player fellow,

I'd camouflage the pigskin

By painting it bright yellow;

We'd then fool our opponents,

And win the game hands high,

'Cause they'd think we had a pumpkin

And were going to make a pie.

Sunday, August 4, 2019

Chicago camouflage artist's wife held for shoplifting

Above World War I-era embedded figure puzzle as published in the St Joseph Daily Press (St Joseph MO), April 16, 1915. Artist unknown.

•••

FINDS MISSING WIFE IS HELD AS SHOPLIFTER in Sioux City Journal (Sioux City IA), April 25, 1922—

Chicago, April 24—A three days' search for a missing wife ended when her husband discovered her in the house of correction serving a 10 days' sentence as a shoplifter.

The women is Mrs. Lilian Norman, 22. Her husband, Frank, is well known as a professional skater, having appeared in the College Inn and other places of entertainment. He is also a commercial painter and during the war was a camouflage artist.

They were married a year and a half ago, and until a month ago they resided in Kansas, which state was the birthplace and home of Mrs. Norman. Four weeks ago they came to Chicago.

Norman believes his wife innocent of the charge of taking a piece of cloth. He says some professional shoplifter, near capture, thrust it in her handbag.

•••

FINDS MISSING WIFE IS HELD AS SHOPLIFTER in Sioux City Journal (Sioux City IA), April 25, 1922—

Chicago, April 24—A three days' search for a missing wife ended when her husband discovered her in the house of correction serving a 10 days' sentence as a shoplifter.

The women is Mrs. Lilian Norman, 22. Her husband, Frank, is well known as a professional skater, having appeared in the College Inn and other places of entertainment. He is also a commercial painter and during the war was a camouflage artist.

They were married a year and a half ago, and until a month ago they resided in Kansas, which state was the birthplace and home of Mrs. Norman. Four weeks ago they came to Chicago.

Norman believes his wife innocent of the charge of taking a piece of cloth. He says some professional shoplifter, near capture, thrust it in her handbag.

Labels:

camo,

camouflage,

embedded figure,

fabric,

graphic design,

puns,

puzzles,

visual pun,

Women,

World War I,

WWI

Brokerage proclivities applied to auto camouflage

|

| Ambulance camouflage in New York (1918) |

Then someone thought up a simple job, that of camouflaging a Ford. I had no overalls but applied and was accepted. Camouflage is so perfectly ridiculous and the paint is applied in such a haphazard fashion that even a college professor or a minister can do that. I turned my attenuated uniform inside out and tackled the car with teeth gritted. Some days later I encountered this car in Tours, not on tour, and felt so ashamed of its appearance that I wanted to hide behind a cathedral. It would have mortified a Cubist or Futurist.

Saturday, August 3, 2019

Cartoonist Cliff Sterrett | Camouflage Catastrophe

Below This camouflage cartoon by American artist Cliff Sterrett (1883-1964) was featured in a comic strip series called Polly and Her Pals. It was published in the Bridgeport Telegram (Bridgeport CT) on September 26, 1918.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)