|

| Portrait of a Lady in a Red Dress by J. Dwight Bridge (n.d.) |

J(ohn) Dwight Bridge was born on December 9, 1893, in St. Louis MO, where his family was socially prominent, wealthy and influential. His ancestors had been among the founders of Washington University. Having moved from Walpole MA to St. Louis, his family “made a fortune” from the railroad and the manufacture of cast-iron stoves.

Dwight attended a prestigious private school in Pawling NY. He then went on to study art at the Art Students League in New York, where he worked with painter, muralist and interior designer

Albert Herter, whose father had co-founded the Herter Brothers interior design firm in New York, and whose son was

Christian Herter, Secretary of State in the Eisenhower administration.

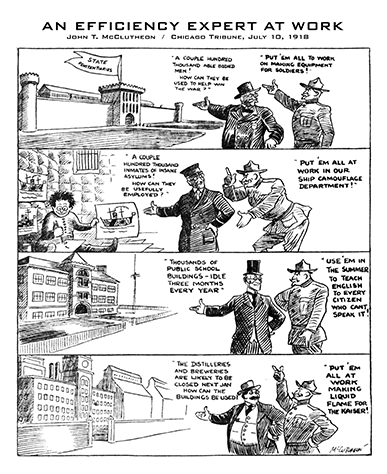

In 1917, having returned to St. Louis, Bridge announced his intention to “give up his career in art to enter the Episcopal ministry.” But when the US entered World War I, he decided instead to enlist as a camouflage artist. In September 1918, when the US Army formed its first camouflage unit, he was among the first to enlist, along with fellow artists

Barry Faulkner (Abbott H. Thayer’s cousin),

Sherry E. Fry,

William Twigg-Smith from Hawaii, and

Everit Herter (son of Albert Herter), who had only recently married.

Appointed Sergeant Major (and soon after First Lieutenant), Bridge was the highest-ranking non-commissioned officer of the group. He shared a tent with the unit’s leading commissioned officer, Lieutenant

Homer Saint-Gaudens, the son of

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the celebrated American sculptor. After months of training at Camp American University in Washington DC, the camouflage unit (officially known as Company A of the 40th Engineers) departed for France at the end of December 1918. In the subsequent months at the front, two members of the unit died in action, including

Everit Herter, who was killed at Chateau-Thierry. Following the war, Bridge lived in Paris, then resettled in New York.

In 1918, five weeks before her husband's death, Everit Herter's wife had given birth to a son named Everit Herter Jr., who never saw his father. Around 1920, Dwight Bridge relocated to Santa Barbara CA, where his former teacher Albert Herter had established a new permanent studio at his mother’s former estate, called

El Mirasol. Bridge married Everit Herter’s widow, Caroline Keck Herter, and thus became the stepfather of Everit Herter Jr. In July 1919, the Herters’ second son, named Albert, died in Santa Barbara at the age of two years and ten months. In their early years of marriage, Dwight Bridge and Caroline Herter Bridge became parents of two of their own sons, Matthew and John Jr.

|

| J. Dwight Bridge (c1933) |

In the 1920s, Bridge’s marriage fell apart. After several years of estrangement, he and his wife obtained a divorce in 1933. At about the same time, Bridge’s father died in St Louis, and he was slated to receive an inheritance of about $100,000 (worth nearly two million dollars today). In newspaper interviews, he revealed that he would refuse to accept it, saying that “an inheritance is more of a hindrance than a help.” Instead, he gave the money to his former wife and their children, and announced that henceforth he would survive as what he called a “vagabond” or “hobo” artist.

He decided to hitchhike somewhat aimlessly around the country (his travels would take him as far as Japan and China) all the time earning his living by painting portraits. Carrying few possessions and almost no money, he began his trek in Salina KS, “the geological center of the United States.” According to a 1933 newspaper story (of which there were many, since his story was rightly regarded as odd, even bizarre), having arrived at Salina at 9:30 in the evening, he “laid all his money—30 cents—and his half-filled package of cigarettes down on the station platform, buried his wedding ring and, although it was night, immediately began a search for employment. He was 40 years old.” He was allowed to sleep in jail that night, and, in the morning, began to hitchhike west, earning his meals and lodging by various means. He was, he explained to reporters, “a man from the East, without any funds, a painter who could whitewash fences and paint doors, portraits or murals.”

The news stories bore fruit. After trading pencil portraits of meals, he was soon receiving commissions for portrait painting. The first was for $200, but he gradually raised the price to $500. On his trip to Japan, where he had eight commissions, he stopped over in Hawaii to see his former fellow camoufleur, William Twigg-Smith, whose relatives owned the newspaper there. From Hawaii, he flew back to the US mainland, then resettled in New York, while also continuing to travel around, from city to city, painting portraits of the rich in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Dayton OH, San Francisco, Palm Beach, Colorado Springs, and elsewhere.

In a 1946 article in the Palm Beach Post, there is a pencil portrait of US Navy Captain Martin L. Marquette, who was then the commanding officer of the Naval Special Hospital (about to be closed) in Palm Beach. The drawing, the article explains, “is the work of J. Dwight Bridge, portrait artist and veteran of both World War I and II, to whom the closing of the hospital will signal a return to civilian life. During the past few months, while recuperating at the hospital, Mr. Bridge as part of his rehabilitation work has got his hand back in sketching by doing 90 portraits of the staff and patients at the hospital...During the war [WWII] he engaged in camouflage work in the AAF [Army Air Force] along similar lines he followed for the engineers in the previous war.”

Three years earlier, one of the Bridges’ sons, John Dwight Bridge Jr, (born 1920), had been killed in action while serving with the US Navy in the Mediterranean.

John Dwight Bridge Sr. died in Palm Beach FL on October 22, 1974.

•••

Sources

Evelyn Burke, “‘Hobo Artist’ Paints Society Folk But He Doesn’t Like Money” in Pittsburgh Press, May 2, 1935.

“Capt. M.L. Marquette” in Palm Beach Post (Palm Beach FL), February 3, 1946.

Helen Clanton, “Hitch-Hiking as a Form of Service” in St. Louis Globe Democrat, January 13, 1936.

“Noted Artist Says Fighting Elements Provides More Thrills Than Many Sports” in Dayton Daily News (Dayton OH), April 15, 1936.

“St. Louisan in Camouflage Unit of US Army Home” In St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 15, 1919, p. 5.

“St. Louisan Who Paid Way Around World as Painter and Portrait He Made” in St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 19, 1933.

•••

SEE ALSO

Nature, Art, and Camouflage (35 min. video talk)

Art, Women’s Rights, and Camouflage (29 min. video talk)

Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage (26 min. video talk)

Art, Gestalt, and Camouflage (28 min. video talk)