Above An assemblage by Romainian surrealist Viktor Brauner (1903-1966), titled Wolf Table (using taxidermy bits from a fox, not a wolf), 1939. Other than their shared interest in taxidermy, there is no explicit connection between Brauner and the story of Arthur J. Coleman below.

•••

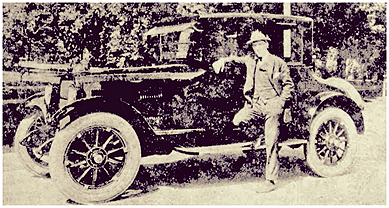

In the 1921 Indianapolis city directory, Arthur J. Coleman is listed as a taxidermist (he was the curator at the Indiana Statehouse Museum) and a custodian, with the home address of 337 South State Avenue. James A. Coleman, his father, shared the same residence, as did Arthur’s mother, Nancy S. Coleman.

In connection with his museum position, Coleman was allowed to carry a gun, a revolver in a shoulder holster. In May 1920, he and three companions (including an eighteen-year-old woman named Floy Minck) were returning to Indianapolis at night, when Coleman, who was driving, noticed that an automobile tire was blocking the road. When he stopped to look more closely, he saw that a rope was attached to the tire, and that it was being pulled off from the side. He heard voices in the dark, and saw six men approaching the car. He drew his revolver and fired two rounds. The men fled and Coleman hurriedly drove off.

In September 1920, Floy Edna Minck (1902-1976) married an Indianapolis carpenter named Bernard B. Bartlett. Ten months later, Arthur J. Coleman married a young woman (the same age as Minck) named Elizabeth (Libby) Schmitter. In November of that same year, there was a jury trial in Indianapolis, in which Coleman was accused of threatening to kill Bartlett, because of a dispute about “a girl whom Bartlett later married” (presumably Floy Minck Bartlett). The jury could not agree on a verdict.

Coleman’s marriage to Libby Schwitter Coleman was an unfortunate pairing. It was troubled from the start, and they agreed to separate at the end of the first year. Coleman moved to New Harmony IN, on the Wabash River, while his wife lived twenty miles west in Crossville IL. They had lived apart for about a year, when, according to Coleman, he received a phone message and a letter from his wife, suggesting that they talk about living together again.

On April 26, 1923, Coleman (this is based on his account) drove to Crossville, to talk to his wife about reconciliation at a house where she was then staying (apparently owned by someone named Jeff Young). When he entered the front door, he was struck on the head from behind and fell to the floor unconscious. When he regained consciousness (he testified), he was lying in a room, with a revolver in his hand. His own revolver was still in his shoulder holster. Nearby was the body of his dead wife, who had died from three or four bullet wounds. In a 1923 news article, it was noted (without explanation) that the owner of the house, Jeff Young, is “an inmate of a hospital for the insane in Illinois.” It was also claimed that a man (unnamed) who was in the house at the time of the shooting had “left immediately and was away from [that area] for a year.”

Despite Coleman’s account of what happened, he was arrested at the site for his wife’s murder, and jailed in Carmi, the county seat. On the day after his arrest, his mother visited him at the jail. She later said: “When I pulled Arthur’s head down to kiss him, I felt a bump on his head and noticed blood on my hand as I left the jail.” But that injury was not mentioned in the documentation for his appeal.

Coleman said that, while he was in jail for three weeks, awaiting his court appearance, the sheriff brought a “professional hangman” to his cell, to describe the agony of dying that way. He was then taken to a window, and shown where the scaffolding would be built. He was told: “That’s where we will stretch your damned neck.” He was also warned about the horror of being lynched if an angry mob would storm the jail.

Coleman later described his condition, while awaiting his court date, as being “sick and nervous.” Inspite of having no memory of the shooting, he decided to plead guilty (to avoid the death penalty) when he appeared before a judge on May 19. He was then sentenced to life in prison for a term of ninety-nine years. He spent the next 21 years at the Illinois state prison at Joliet as well as on a prison farm.

[So what does any of this have to do with camouflage? Aha, I thought you’d never ask.]

It seems that during his confinement, Coleman continued his interest in taxidermy, including animal camouflage, sculpture, landscape design, and museum exhibitions. Various people, including other inmates, congressmen, and well-known citizens (soprano Mary Garden being one) spoke in favor of his work. He was permitted to open a shop inside the prison, and “because of his genius,” a campaign was started to allow him to be pardoned. It did not succeed.

When the US entered World War II, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was a further effort to secure Coleman's release in exchange for advising the army on wartime camouflage. An article described him as “one of the best camouflage artists in the United States.” According to another account, he was “a nationally-known taxidermist and artist” who has “taken up camouflaging” and whose “services were wanted to help camouflage coast artillery batteries.” But that appeal was also denied.

In the end, Arthur J. Coleman was not pardoned, but he was released on parole on July 27, 1944, having served 21 years of his life sentence. Thereafter, he earned his living as a professional taxidermist. As late as April 1960, he owned a taxidermy shop (specializing in “game fish and big game mounts”) in Boca Raton FL.

Below is the most complete source of information about Coleman's life, consisting of two pages in the Indianapolis Times, September 12, 1932, pp. 1 and 3.

SEE ALSO

Nature, Art, and Camouflage (35 min. video talk)

Art, Women’s Rights, and Camouflage (29 min. video talk)

Embedded Figures, Art, and Camouflage (26 min. video talk)