A blog for clarifying and continuing the findings that were published in Camoupedia: A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage, by Roy R. Behrens (Bobolink Books, 2009).

Sunday, July 17, 2022

exhibition video / National Maritime Museum in Brest

I have recently been notified by the museum’s director, Jean-Yves Besselièvre, that a video about the exhibition is now available online at this link. Reproduced here above and below on this blog page are several screen grabs from the video, including some of the ship models and the dazzle-painted building that houses the design firm.

lowly looking car made quite snappy by paint & brush

AUTO GOSSIP in The Times (Munster IN), February 2, 1920, p. 6—

Old Man Snodgrass, of the Auto Customs Shop, is the adeptest camouflage artist you ever saw. Not boasting at all, but says Art: “People have the doggonest time telling my work from new cars, but the difference is so little few people can tell.” What do you charge, Mr. Snodgrass, for painting a 1914 Lizzie that’s only “went” 211,999 miles? Will she look like new when you get through?

•••

Anon, CAMOUFLAGE USED ON CAR: Lowly Looking Car Made Quite Snappy By Use of Paint and Brush: Wartime Treatment of Shipping Used to Improve Motor’s Appearance, in The Daily Colorist, June 1929—

Does your car look too fat, too tall, too short, or just generally antique?

Cheer up. Just study a few good camouflage methods and you can with paint endow it with the lines of the finest racer. The dress principle that makes stout ladies look thin through vertical-lined clothes works for cars, too.

Camouflag[ing] autos to make them look larger, lower, more luxurious is the job of Captain H. Ledyard Towle, alumnus of Adelphi Academy and Pratt Institute of Brooklyn.

Before the war nothing was known of Captain Towle’s new kind of art. Now he has applied the principles of camouflage…to the painting of automobiles.

“Tommyrot,” the auto manufacturers told him when he first submitted his ideas. “A car is a car. You can’t improve its engine or even its appearance through camouflage.”

But they gave him a chance. He went quietly to work and repainted one model. Its sales increased with astounding rapidity. Now he supervises the painting of millions of them.

He got his ideas during the war. Before that he was a portrait painter. Previous to the age of thirty he had done the portraits of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker and other distinguished persons. Then during the war he acquired a more humble idea of art.

He learned that love of beauty and symmetry is not confined to the upper crust. The ordinary run of soldiers, the small farmer, the street cleaner, everyone, in fact, knows when something beautiful has been set before him.…

One of his experiments affecting the neatness of a car’s appearance consisted of taking a dark-colored car and painting a light strip along its entire length on a level with the top of the radiator.

Saturday, July 16, 2022

charts explaining the purpose of WWI ship camouflage

|

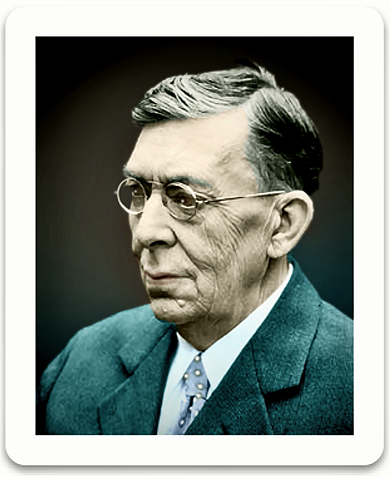

| Cover image showing Everett L. Warner |

During World War I, it appears that he worked with the US Navy’s Camouflage Section in 1917-18 in Washington DC. He can be found in newspaper archives because he was prone to writing letters to the editor. In one of those (in Camouflage and Sea in The Boston Herald, November 19, 1933, p. 10), he writes as follows—

During the World War, I was given special duties by naval authorities in Washington to compose charts explaining the fundamental purpose of camouflage, so that all officers on ships and in army headquarters would not be so befuddled as to what it was all about. Although but just out of my “teens,” I found it to be a very serious hindrance in the conduct of martial affairs to have certain scientific, over-practical officials treat the subject lightly, because their training had precluded knowledge of the subject, when it was essential that pilots know why certain razzle-dazzle designs appeared to throw a vessel several points off her course, and why our aerial bombers did not know something about the uncanny European artistry of obscuring cannon locations and so on.

More complete information about Gifford and his wartime assignment has so far been a challenge. In addition to portrait painting, he was apparently also an etcher, newspaper and magazine illustrator, stage set designer, bookplate designer, teacher, and writer. He seems to have studied at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fenway School of Illustration, Livingston Pratt Stage Design School, and the New York School of Applied Art.

He registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, in Plymouth County MA, at which time he gave his birth year as 1894, not 1895, as is mistakenly cited in various biographical notes. In a newspaper article (Boston Globe, August 14, 1919, p. 11), his artwork is listed as included in a 1919 Duxbury exhibit which also featured artworks by (among others, including several camoufleurs) Charles Bittinger and Everett Longley Warner, both of whom would have been among Gifford’s supervisors in his camouflage-related work.

Thursday, July 14, 2022

real camouflage would not be visible in a photograph

Above Cover of Railroad Stories magazine, January 1932, supposedly showing the camouflage of an Allied railroad engine during World War I. The illustration is by Emmett Watson (1893-1955), whose work was widely published in popular newsstand magazines between the World Wars.

Emmett Watson (c1932)

•••

Robert K. Tomlin, American engineers behind the battle lines in France. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1918—

It is obvious that this subject [wartime camouflage] cannot be written about in detail. The familiar illustrations often published in magazines and newspapers are the obvious and theatrical ones, seldom used. The real camouflage would not make an interesting picture, because no one would see it in a photograph.

Tuesday, July 12, 2022

taken round back the warehouse and painted brown

Above One of the slides from a talk I’ve given on the Pre-Raphaelite artists of the 19th century, showing how John Everett Millais made use of edge alignment, symbolism, and broken continuity (thereby triggering closure) in his painting titled Christ in the Carpenter’s Shop (1849-50).

•••

As described in a news article, Millais’ grandson was the portrait painter Heskith Raoul Lejarderay Millais, known as “Liony” Millais. His grandmother was of course Effie Gray (well-known for the annulment of her marriage to John Ruskin), and his father was the artist and travel writer John Guille Millais.

Raoul Millais was especially known for his paintings of horses, as was his friend and contemporary Alfred Munnings. Both were outspoken critics of the work of Picasso and other avant-garde Modernists. It is said of Munnings that “When his light grey Arab horse Maharajah was refused boarding to sail to the Boer War ‘for reasons of camouflage,’ he took it round the back of the warehouse and dyed it brown.”

Despite his age, and various physical injuries from hunting, Millais served in the Scots Guards during World War II, in the process of which he commanded the military unit that guarded Rudolf Hess—who “spoke very good English and seemed to be the most unlikely Nazi.”

•••

ARTIST WANTS TO CAMOUFLAGE in Sunday Times (Perth, Western Australia), January 28, 1940, p. 2—

London—One of the artists whose name has been submitted to the [British] War Office for camouflage work is Mr. Raoul Millais, grandson of Sir John Millais, the pre-Raphaelite painter who became president of the Royal Academy.

Mr. Millais has so far specialized in portraits of people and horses. A member of the Beaufort Hunt, Mr. Millais has painted several horses belonging to his fellow followers of the pack.

His most notable horse subject was Blandford, the sire of several Derby winners.

Monday, July 11, 2022

grew out of his interests in color and interior design

|

| William Andrew Mackay |

We’ve written and self-published (and made available free online) what is undoubtedly the most detailed account of how he became interested in camouflage, and what he accomplished during the war [see sample page below]. It arose from his interests in color and his extensive experience as an interior designer.

|

| Page from essay on Mackay |

That said, he remains an enigma in certain respects. For example, we know that he established a somewhat underhanded school (since all ship camouflage at the time was officially required to be designed by US Navy personnel, not by civilians) for wartime ship camoufleurs at his design studio at 345 East 33rd Street in Manhattan. Over time, he worked with at least sixty students, some of whom would become the country’s finest camoufleurs. There is a partial list of those who studied with him, including some who later served under Everett L. Warner at the US Navy’s Camouflage Section in Washington DC.

We have also found a brief article from Arts News (Vol 17, 1918) with the heading Marine Camouflage Course at Columbia, which reveals that Mackay was planning to teach a course on ship camouflage at Columbia University, beginning in mid-November that year. However, the war would end just seven days before the first class meeting, so most likely the class was cancelled. Here is the text of the news article—

Columbia University announces a course in the elements of concealment and disguise as applied to ships. By arrangement with William Andrew Mackay, District Camoufleur of the Energency Fleet Corportion, and under the administration of the Department of Extension Teaching, the university will offer, beginning November 18 next, a course of instruction in marine camouflage, covering a period of twelve weeks.

This course will be open to both men and women.

Artists and mature students in various branches, painters, architects, photographers, advanced art students, poster and advertising artists, students of shipping and ship design, and others of allied qualifications, will be eligible for admission, subject to the approval of the university…

more>>

Sunday, July 10, 2022

standing behind and above, painting faces on his head

|

| Painting by Frederick Rhodes Sisson (c1920-21) |

Amherst College is to hear lectures on camouflage in the Plant Protection School. Frederick R. Sisson, instructor of drawing and painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, who has been conducting a course in camouflage there, to which students of Brown University are admitted, has been chosen for the task. Mr. Sisson acts also as critic of the Providence RI Journal.

We have mentioned Frederick Rhodes Sisson (1893-1962) in two earlier blog posts, here and here, in connection with his role as a studio assistant (one of three) to the well-known American painter Abbott Handerson Thayer. The other two assistants, in the last years of Thayer’s life, were Henry O’Connor, and David O. Reasoner, who would later become Thayer’s son in law, and who was a civilian ship camoufleur during WWI.

It is of particular interest to learn that Sisson lectured on camouflage at Amherst and RISD, since Thayer is regarded as a pioneering expert on protective coloration and natural camouflage, and is commonly referred to as the “father of camouflage.”

Sisson had two connections with RISD. Having grown up in Providence, he was a student at RISD prior to World War I, and then returned to teach there from 1924-1952. He was also an art critic for the Providence Journal from 1932-1950. When he retired in 1952, he moved to Falmouth MA, where he died ten years later.

RISD is at the center of this for another reason, as we have discussed in earlier posts. The Fleet Library at RISD is among the leading archival resources for the research of ship camouflage. One of the WWI American ship camoufleurs, who oversaw the painting of ships in the harbor, was an artist named Maurice L. Freedman. When the war ended in 1919, Freedman entered RISD as a student, and while there, he gave the art school his set of 450 color lithographic plans for American ship camouflage. It is a rare and remarkable resource. More information about it is here.

We also bring this up because, in recent years, there was an online notice about the sale of a painting attributed to Sisson (reproduced above), unsigned and undated, but stamped as part of his estate. It was labeled on the online post as a “3/4 portrait of Abbott Thayer in his later years.” I myself find it hard to believe that this is a portrait of Thayer. Sisson was presumably a capable painter. Indeed, among his responsibilities while working in Thayer’s studio was that of being able to make accurate copies of paintings that Thayer had started. This would then enable Thayer to complete his original painting, as well as apprentices’ copies, in differing ways, without spoiling the original effort.

Knowing that, one would expect a Sisson portrait of Thayer to be a convincing likeness of its aging sitter—which it is to a certain extent. What then is wrong with this picture? The most glaring problem is the hair. Thayer had begun to grow bald at a fairly early age. He had no hair on the top of his head, which prompted his children to refer to him as Shakespeare. Indeed, his bald pate was so hairless at top that his children amused themselves (and him) by standing behind and above him and painting faces on his head. So, one is led to wonder about the indentity of the sitter. The elderly man in the portrait has a receding hairline—that’s for certain—but he is far from bald on top and back.