According to the text on a postcard, this is a "French Renault Tank used in the [First] World War by the Republic of France…[and] is one of a

number that was given to the United States in partial payment of the

French War Debt. It still retains its original number, R.F. 2324 as it

did during the war. This tank was presented to the James L. Noble

Post, No. 3, Veterans of Foreign Wars of Altoona PA and was put in

commission by members of that post."

A blog for clarifying and continuing the findings that were published in Camoupedia: A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage, by Roy R. Behrens (Bobolink Books, 2009).

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Monday, April 23, 2012

Dazzle Camouflage on BBC-TV

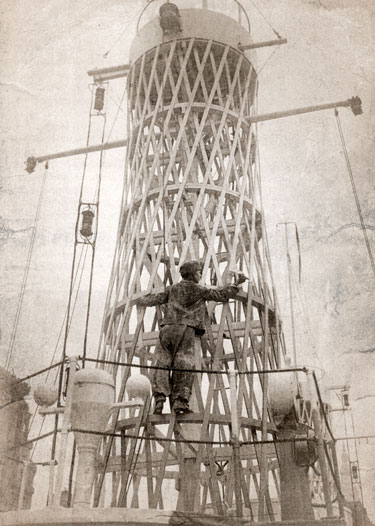

Last week, BBC-TV ran a four-minute video on World War I ship camouflage, featuring an interview by John Sergeant on The One Show with UK scientist Nicholas Scott-Samuel. Here it is on YouTube. Note the copy of SHIP SHAPE: A Dazzle Camouflage Sourcebook (2012) on the table in the clip. Above (not from the program) is a photograph of a camouflaged US transport ship, arriving at Liverpool, as reproduced in War of Nations (1919).

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Kissel Kar Kamouflage

This is a newspaper ad for a 1917 Kissel Kar ("Every Inch a Car"), manufactured by the Kissel Motor Car Company in Hartford WI. The company was founded in 1906 by Louis Kissel and his sons, who were owners of the firm until 1930. In addition to motor cars, the Kissels manufactured trucks (see below), hearses, fire trucks, taxis and utility vehicles.

During World War I, a news article in Motor West (October 15, 1917, p. 8) announced that W.L. Hughson (president of the Pacific Kissel Kar branch)—

has donated the famous Kissel military scout car, recently used to blaze the 'three nation run,' to the government department having the new operations of 'camouflage' in its charge. A committee of three prominent San Francisco artists will paint this car with color patches, which suggests nothing except the surrounding earth, trees, grain fields, sky, etc., making an exact facsimile of the cars now being used by the allies along the various war fronts.

During World War I, a news article in Motor West (October 15, 1917, p. 8) announced that W.L. Hughson (president of the Pacific Kissel Kar branch)—

has donated the famous Kissel military scout car, recently used to blaze the 'three nation run,' to the government department having the new operations of 'camouflage' in its charge. A committee of three prominent San Francisco artists will paint this car with color patches, which suggests nothing except the surrounding earth, trees, grain fields, sky, etc., making an exact facsimile of the cars now being used by the allies along the various war fronts.

In an issue of the Oakland Tribune ("Artist Are to Paint Motors, Plan 'Camouflage Carriages'," September 2, 1917, p. 32), it was stated that the three "prominent artists" on the Kissel Kar camouflage committee were architect Arthur Brown Jr, and artists [Ernest] Bruce Nelson and A. Sheldon Pennoyer. They were chairman, assistant chairman, and secretary, respectively, of the American Camouflage Western Division, as reported in "San Francisco Architects and Artists as Camoufleurs" in The Architect and Engineer of California (Vol 1 No 2, August 1917, p. 58).

In a later issue of the Oakland Tribune ("First Camouflage Auto Is Let Loose," October 28, 1917, p. 45), a second article reported on the progress of the touring camouflaged Kissel Military Highway Scout—

America's first camouflaged automobile has been let loose, and is now on the war path. The inhabitants of the Pacific Coast from Seattle to San Diego swear they are 'seeing things.' A sheriff who has a record for pinching speeders is out after the camoufleurs who committed 'camouflage' to prove that America's automobiles are as chameleon-like while on the war path as those in Europe.

For be it known that the military scout Kissel Kar of 'three-nation-fame' has emerged from the hands of the artists and is now keeping the sheriffs, police and judges sitting up nights planning how they can capture a thing they cannot see.

Reports from different points along the Pacific highway are to the effect that the car is practically invisible at a short distance. Its peculiar grassy marks blend in with its surroundings. Spots of green and pink with dabs of brown and red give such a mottled effect that no matter what speed it is going as far as the eye is concerned it registers 'here it comes and there it goes.'

That automobilists are taking a keen interest in the art of camouflaging is evident from the way the Kissel Motor Car Company is being besieged by inquiries from motorists for further information relative to painting automobiles so that they will not be discernible at a distance…

Small town constables through whose municipalities the car has gone, have sworn that they thought the whole scenery was rolling in on them, and were so astonished and surprised that they did not realize the car had passed them at a Ralph DePalma clip…

In a later issue of the Oakland Tribune ("First Camouflage Auto Is Let Loose," October 28, 1917, p. 45), a second article reported on the progress of the touring camouflaged Kissel Military Highway Scout—

America's first camouflaged automobile has been let loose, and is now on the war path. The inhabitants of the Pacific Coast from Seattle to San Diego swear they are 'seeing things.' A sheriff who has a record for pinching speeders is out after the camoufleurs who committed 'camouflage' to prove that America's automobiles are as chameleon-like while on the war path as those in Europe.

For be it known that the military scout Kissel Kar of 'three-nation-fame' has emerged from the hands of the artists and is now keeping the sheriffs, police and judges sitting up nights planning how they can capture a thing they cannot see.

Reports from different points along the Pacific highway are to the effect that the car is practically invisible at a short distance. Its peculiar grassy marks blend in with its surroundings. Spots of green and pink with dabs of brown and red give such a mottled effect that no matter what speed it is going as far as the eye is concerned it registers 'here it comes and there it goes.'

That automobilists are taking a keen interest in the art of camouflaging is evident from the way the Kissel Motor Car Company is being besieged by inquiries from motorists for further information relative to painting automobiles so that they will not be discernible at a distance…

Small town constables through whose municipalities the car has gone, have sworn that they thought the whole scenery was rolling in on them, and were so astonished and surprised that they did not realize the car had passed them at a Ralph DePalma clip…

There are a handful of 1917 photographs here (mistakenly dated "1920s," and claiming to be "copyright protected") of the touring Kissel Military Highway Scout, dressed in disruptive camouflage garb.

We have also found a photograph (below) of trucks produced by Kissel, with camouflage applied, being shipped to Europe. The camouflage pattern on each is unique.

We have also found a photograph (below) of trucks produced by Kissel, with camouflage applied, being shipped to Europe. The camouflage pattern on each is unique.

|

| WWI camouflaged Kissel trucks |

Thursday, April 12, 2012

Camouflage Amusement Ride

|

| Camouflaged tank amusement ride (1920) |

World War I ended in 1919. A year later, in the January 1920 issue of Popular Mechanics, there was a short illustrated article about a new amusement ride, with the headline "Rough-Riding Tank as Amusement Car" (p. 113). As shown by the illustration above, it consisted of—

a set of four counterfeit tanks, dressed in camouflage paint, that bump around the inside of a wooden bowl with about an acre of surface. The make-believes are light, with transverse seats like a street car, and run on wheels instead of crawling on a flat tread; but they stagger along over carefully designed bumps and rough spots with satisfying realism…As an electric motor in the base rotates the tower, centrifugal force carries the tanks nearer and nearer the edge of the bowl, adding further zest to the adventure.

Notice there's a close-up view of one of the tanks in the bottom left corner of the illustration.

Actually, there was an even earlier link between amusement rides and camouflage, as shown by the two photographs below. As early as 1896, there were American amusement rides that were widely known as "razzle dazzle" (you can see that printed on a sign on the striped merry-go-round amusement ride in the first photo). In the same year, artist and naturalist Abbott H. Thayer began to publish his theories about protective coloration in nature, and now and then he used the terms "dazzle" and "razzle dazzle" in reference to high difference or disruptive camouflage. I suspect he was alluding to these popular amusement rides.

|

| Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs (c1896) |

Camouflage Textiles | Valerie Keating

|

| Dazzle-based knit textiles by Valerie Keating |

Designer Valerie Keating is a BA graduate from the School of Design at the Glasgow School of Art. Among the works that she produced for her portfolio was a Ship Shape: Dazzle Camouflage Collection, a series of innovative textiles (made with an industrial knitting machine), "inspired by the bold patterns of dazzle camouflage used by the Navy during the First World War." >>more…

Sunday, April 8, 2012

Camouflage Artist | Ezra Winter

|

| The Ezra Winter Project (online) |

American artist Ezra Winter (1886-1949) was born near Traverse City MI. He attended Olivet College (in Michigan), then studied in Chicago at the School of the Art Institute, where he graduated in 1911. In the same year, he won the prestigious Prix de Rome, by which he was able to study for three years at the American Academy in Rome. Winter's prize was in the category of painting, for what was described in a news story at the time as "a large canvas called The Arts, a beautiful and graceful work." A young Denver architect, George Simpson Keyl , received the same prize in that category, while the Prix de Rome in sculpture that year was awarded to Harry Dickinson Thrasher.

Thrasher had grown up in Plainfield NH, where he had been a student of the most famous American sculptor at the turn of the century, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. As Thrasher was growing up, among his friends were Saint-Gaudens' son, named Homer (a theatre designer and, later, an arts administrator), and a young painter from Dublin NH named Barry Faulkner (he was a cousin and student of Abbott Handerson Thayer, the so-called "father of camouflage," and had studied with Augustus Saint-Gaudens as well). Later, Faulkner became a prominent muralist, and a friend of Ezra Winter, with whom he collaborated on several major projects.

When the US entered World War I, a unit for camouflage artists was formed by the US Army. One of the officers in charge of that unit was Homer Saint-Gaudens, while among the very first artists to join were Barry Faulkner and Harry Dickinson Thrasher. After a period of training on the grounds of the American University near Washington DC, their unit was deployed to France at the end of 1917. Of the camoufleurs, there were only two who didn't return—Everett A. Herter (the brother of US diplomat Christian Herter) and Harry Thrasher, both of whom were killed in France in 1918. Faulkner delivered the eulogy at Thrasher's funeral.

At the same time, Ezra Winter was in New York, where, as a civilian, he worked for the US Shipping Board, as a member of one of thirteen teams of camouflage artists (stationed at various ports around the country) who supervised the painting of dazzle camouflage schemes on thousands of commercial ships (called merchant ships). In charge of the unit that Winter was in was another prominent muralist, William Andrew Mackay. According to official policy, the artists assigned to ship painting were not responsible for the design of the camouflage plans, only for applying them.

Instead, the initial camouflage plans were designed by another team of artists at the Navy's Camouflage Section in Washington DC (there was another research group, largely made up of scientists, at the Eastman Kodak Laboratories in Rochester NY). The DC team of artists made wooden scale models of merchant ships, applied experimental patterns to them, and tested their effectiveness in an observation theatre. The patterns that worked the best were then drawn up, printed in multiples as color lithographs, and sent out to the various harbors, where they served as a "blueprint" while painting the ships.

One of the artists in the Navy's DC camouflage team (the group that actually designed the camouflage patterns) was a British-born American sculptor named John Gregory. There are photographs of him, seated in a room with other camouflage artists (Everett L. Warner, Frederick Waugh, Gordon Stevenson, and others), painting camouflage patterns on miniature ships.

Ezra Winter is not in these photos of course, because he was attached to Mackay's unit in New York. But he is in other photographs (taken shortly after the war) when, as he worked on commissions (one of which was the interior of the Cunard Building in New York), he was photographed with two of his collaborators—his fellow wartime camoufleurs Barry Faulkner and John Gregory.

...

For more on Ezra Winter, see The Ezra Winter Project by Jessica Helfand, who is co-founder of a Connecticut-based design studio called Winterhouse—located in Ezra Winter's former home and studio in Falls Village CT. As of this posting, three Winter-related installments have been issued, the most recent two at here and here.

Friday, April 6, 2012

Camouflage Artist | Maurice (Jake) Day

|

| Frank S. Nicholson, National Park Service Poster (c1938) |

It turns out that the artist in the Disney Studios who determined what Bambi would look like was also a World War I ship camoufleur. His name was Maurice (Jake) Day (1892-1983).

There is an online biography of Day, written by Andrew Vietze, titled "The Mainer Who Found Bambi" (DownEast.com, December 2009).

Here's an excerpt that pertains to his service as a camoufleur—

Born in Damariscotta [ME] in 1892, Jake Day attended high school at Lincoln Academy, where he did his first serious painting of a local church. From there he moved on to the Massachusetts Normal School, studying for a year before transferring to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Upon graduation he found the world embroiled in a war and enlisted in the Naval Camouflage Department of the Emergency Fleet Corps in New Orleans.

As a ship camoufleur in New Orleans, Jake Day presumably worked with Paul F. Brown, whom we featured in a recent earlier post.

The Vietze article provides a substantial account of Day's experiences as an animator in California, where he moved in 1935. One of the firms he worked for was the Walt Disney Studio, which had just purchased the rights to an Austrian children's book about a fawn named Bambi. Disney planned to make an animated film, basing the look of the young deer on a California mule deer. Day convinced Disney to used a white-tailed deer instead—and the rest is history.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Women Camouflage USS Recruit

In an earlier post, we talked about a landlocked navy recruiting station, built in New York in Union Square in 1917. A wooden replica of a ship, it was known as the USS Recruit. As shown in the photographs above, it was initially battleship gray, but in July of 1918, it was repainted overnight in brightly-colored dazzle camouflage by twenty-four members of the Women's Reserve Camouflage Corps. There are historic photographs of the ship being painted (see below), but we have yet to find a photo of the completed camouflage.

Meanwhile, we have run across a news article in the New York Times, titled "CAMOUFLAGE THE RECRUIT: Women's Service Corps Redecorate the Landship in Union Square" (July 12, 1918). Here is the article, which claims that the Recruit's camouflage was designed by American artist William Andrew Mackay. In addition, it includes a list of the women who participated—

The Camouflage Corps of the National League for Woman's Service redecorated the good ship Recruit in Union Square light night and made a neat job of it in spite of the threatening storm clouds and the fact that it was their first painting experience aboard ship. The camouflage idea came from Commander W.T. Conn, who besides getting men for the navy, is also in charge of the famous land ship.

Twenty-four members of the corps, under the command of Captain Myrta Hanford, assisted by a squad of sailors, worked under the direction of Worden Wood, who is now designing rainbows to cover the sides of the vessels of the United States Shipping Board. The dress of the Recruit was designed by William A. Mackay, head camoufleur of the Shipping Board, and it represented a liberal sprinkling of black, white, pink, green and blue, arranged in the most effective manner for avoiding submarines.

|

| additional information |